Mugshots and Camera Fiends

Anika Burgess on how photography transformed 19th century public life

This week: A photography essay and a book giveaway!

I’ll keep my introduction brief since there's a lot to cover in today’s post. Many of you know that I am passionate about photography and all things visual media. I was delighted when I discovered Anika Burgess’ latest book, Flashes of Brilliance: The Genius of Early Photography and How It Transformed Art, Science, and History, this summer, and I immediately reached out to her, asking if we could arrange a Zoom call to meet.

Anika is brilliant and delightful, and after talking for nearly an hour, I realized we should collaborate on something together. So I asked if she’d be interested in publishing an excerpt from her book here on FlakPhoto Digest, and I was thrilled when she agreed. It’s taken some time to get it together, and it’s finally here. As a token of my appreciation for you, dear reader, we’re giving away two copies of Anika’s book — you can read more about how that works below the essay.

Flashes of Brilliance is filled with intriguing stories about the technological history of this medium we all cherish. As Marshall McLuhan said many years ago, “We shape the tools, and the tools shape us.” That’s definitely true with photography, and once images could be fixed and circulated in the culture, the world was never the same. This week, we’re sharing a short piece about 19th-century photography that will entertain and fascinate you. And, funnily enough, the situations Anika describes don’t sound too far off from our contemporary visual culture. I could say more, but I think I should let Anika’s words speak for themselves. I’ll let her take it from here. Enjoy!

As amateur clubs proliferated, so too did a new kind of amateur photographer, one who committed far worse sins than just poorly composed snapshots of trips to the Welsh seaside. This category of amateur even had its own moniker, which described any obnoxious, overeager photographer who possessed few skills and even fewer manners: the camera fiend.

“This fiend in human shape delights in portraying his acquaintances in all sorts of ridiculous situations,” griped the British Journal Photographic Almanac in 1885, as it described the “colossal” army of amateur photographic types. For the fiend, nothing was off-limits. One report complained about a camera fiend stopping a fire truck, mid-emergency, to take a photo. In an anonymously written article from 1893 titled “Confessions of a Snap-Shot Fiend,” the author proudly described his candid photos of Otto von Bismarck, the former German chancellor, tying his shoe, and one that showed a duchess chewing on a large piece of pear.

The camera fiend’s prying photographs were regarded as unwelcome, unflattering, and embarrassing. Amateur photography was embraced by both men and women, but complaints about the male fiend’s activities around women were numerous. “Many estimable young women gave up bathing in the surf for fear their lower limbs would adorn somebody’s photograph album,” reported The American Journal of Photography. The British Journal of Photography said that the conduct of amateur photographers seeking a seaside snapshot “is highly reprehensible, and tends to bring photography into contempt,” adding that women “have a very strong objection to being photographed, surreptitiously, when they are in a state of deshabille.” Another writer reported, in 1889, a “brotherhood of Peeping Toms” in the Berkshires who waited for women to climb out of their vehicle and snap “a glimpse of feminine draperies and hose and record it for future use.”

Some fiends used their photos for genuinely devilish purposes. The scheme was simple: photograph someone—either a woman or a man and a woman together—in a pose that was either embarrassing or suggestive, then make her buy the negatives. In 1891 in New York City, a camera fiend was “haunting” Fifth Avenue, “making snap shots of every pretty woman he meets. Then in a few days he appears at the house of the lady and offers to sell the photograph.” Later the same year, The Photographic Times and American Photographer warned of an amateur “doing a blackmailing business among certain Philadelphia society belles at the shore.”

The rich and famous were also popular targets for the camera fiend. In 1887, a photographer captured an unprecedented candid photograph of Queen Victoria laughing in her carriage during her golden jubilee celebrations, which he published and displayed in a London shop window. The British Journal of Photography commiserated with Her Majesty for the “unfortunate incident,” although the Edinburgh Evening News was decidedly less empathetic: “it is said to be the best portrait that has been taken of the Queen since 1861.” In the United States, Newport society was plagued by camera fiends, resulting in one incident where William K. Vanderbilt II assaulted a photographer and grabbed his camera. In 1901, President Roosevelt blocked off public access to the rear grounds of the White House because of “ill-mannered camera carriers.”

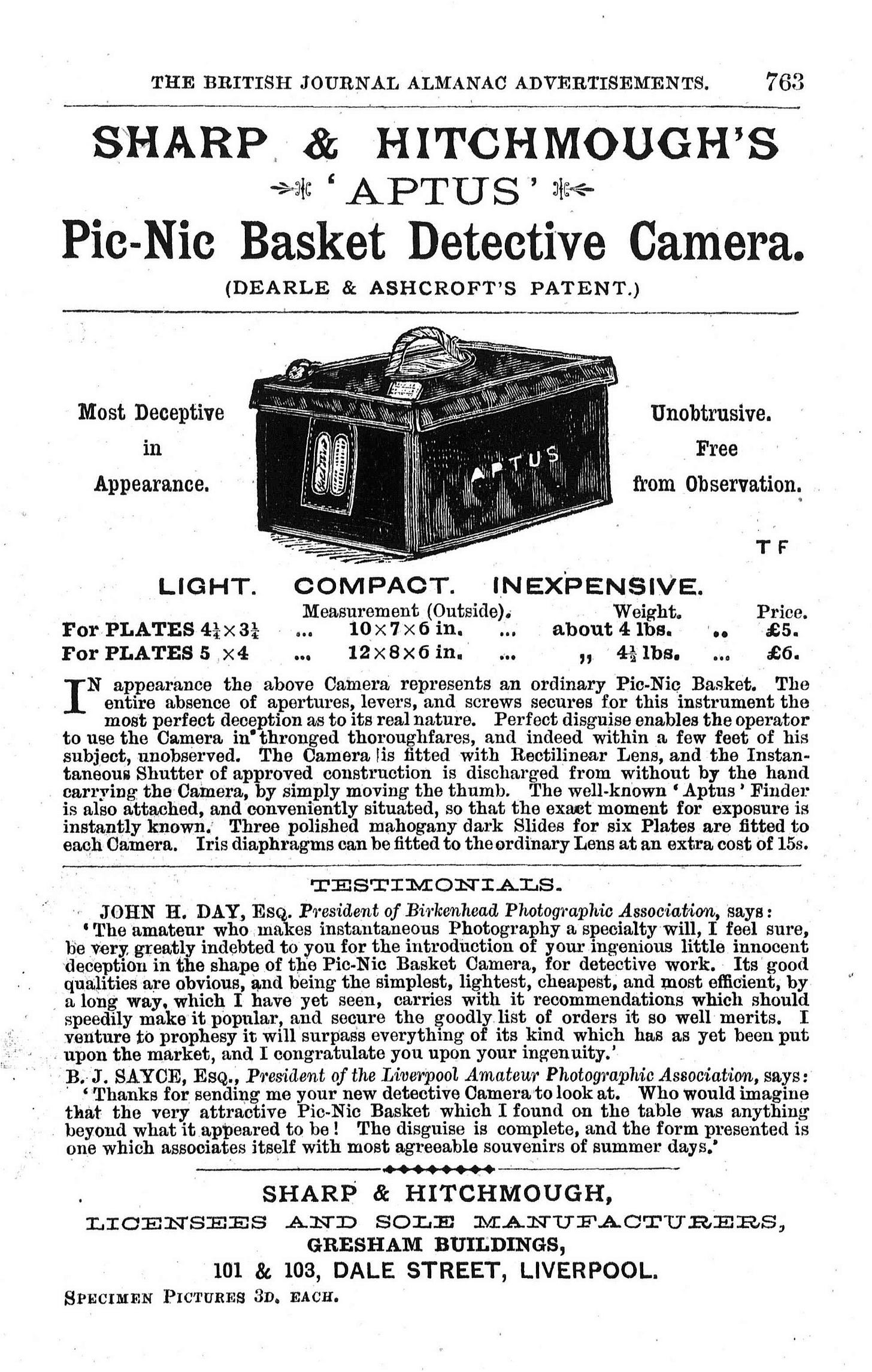

If the fiend had an enabler, it was the detective camera. Hand cameras were easy to use and portable; a detective camera was all this, but in disguise. At its simplest, it looked like a plain box or parcel. “It requires no skill other than to get within range of focus of the unsuspecting victim,” boasted an advertisement for Scovill Detective Cameras, from 1887. One tricky design was the “Deceptive Angle Graphic,” a camera with fake stereograph lenses in the front, so the photographer could snap his subjects at a right angle while he was seemingly looking the other way. In the advertisement, a man was shown using the camera on two women in bathing costumes.

At the Henry Slater Detective Agency in London, the detective camera lived up to its name in the most literal sense: the agency advertised “instantaneous photography” services “for secretly securing photographs of persons when together or separately, for identification and corroboration.” Similarly, in 1888, a newspaper reported—under the heading “Midnight Hunt for Divorce”—that a man had used a detective camera (and magnesium flash) to barge into a hotel and catch his wife having an affair.

Disguised cameras soon began to appear on the market with the sole purpose of taking someone’s photo on the sly. These cameras were typically of poor quality, but highly inventive in how they were concealed. “Most Deceptive in Appearance,” stated an advertisement for a camera disguised as a picnic basket. Other hidden camera disguises included a hat, tie pin, scarf, briefcase, book, watch, handbag, walking stick, and binoculars. One lawyer even had a bespoke camera made to resemble volumes of law books, possibly to capture all those fascinating candid photographs of client meetings. One extraordinary archive of secret photographs still survives in a museum in Norway, shot with a camera hidden behind a buttonhole.

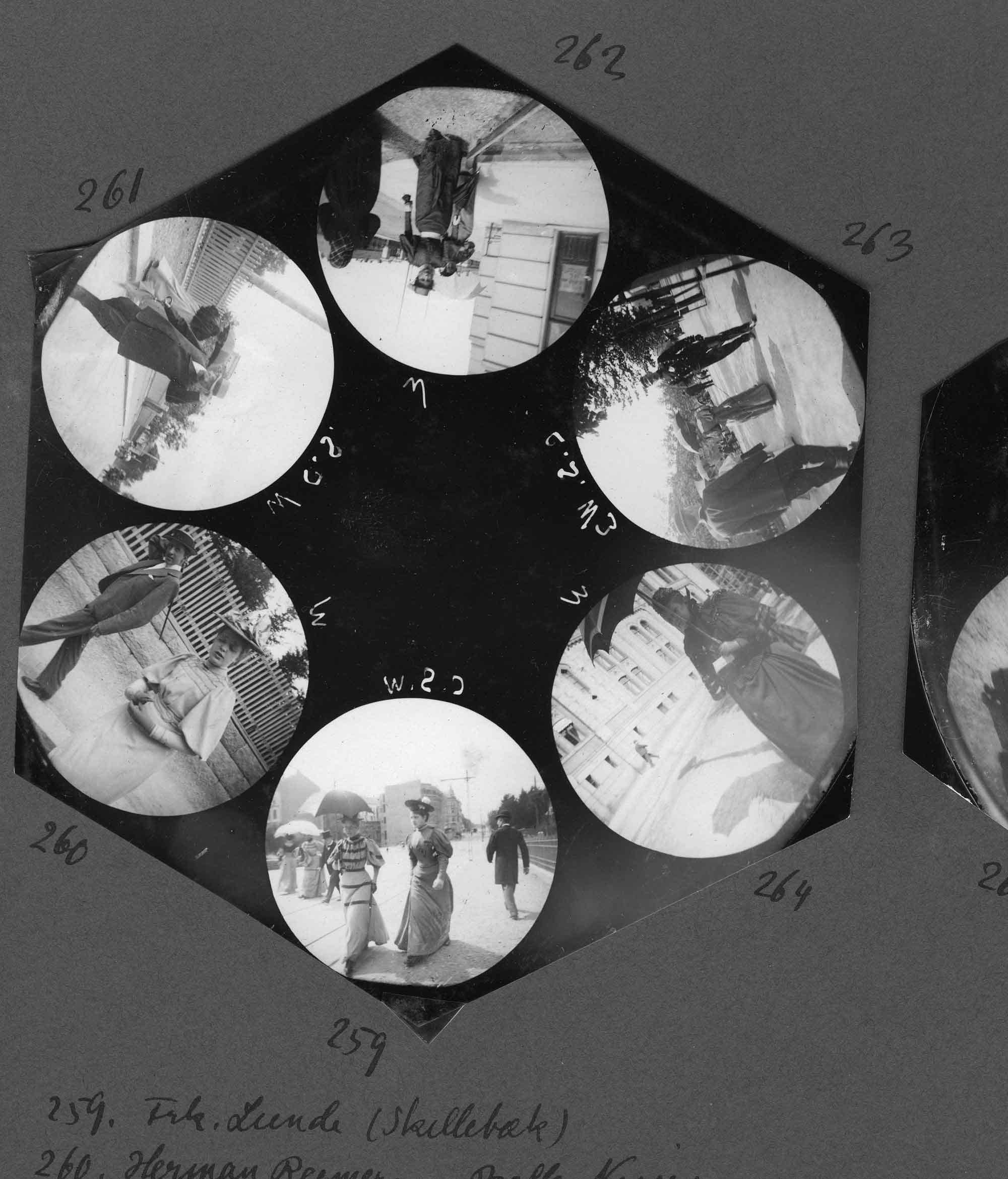

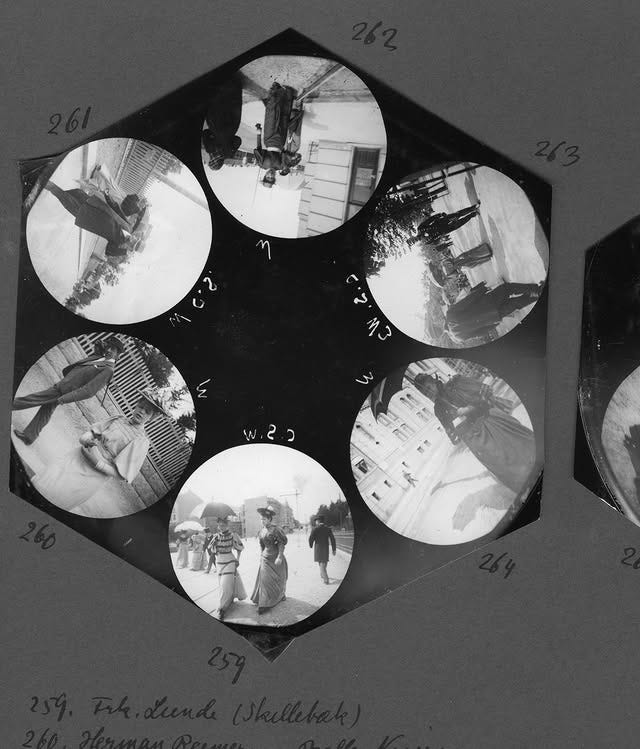

Carl Størmer was a young university student in the 1890s when he began to take secret photographs of street scenes in Oslo. The camera, which was patented in 1886, was disk-shaped and worn around the neck on a chain and positioned under a waistcoat. The lens poked through a buttonhole. On each plate there were six circular negatives, which Størmer rotated with a small knob. When he pulled a concealed string, the camera made an exposure. Størmer had initially bought the camera to take a photograph of a woman whom he had a crush on. (He also took photographs of women swimming.)

Størmer’s archive of circular glass negatives is held at the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology, along with some of his scientific photographs. (Størmer became a well-known mathematician and astrophysicist, and also took photos of the aurora borealis.) His son donated his buttonhole images nearly one hundred years after they were taken, and they are an important record of how people used concealed cameras. Størmer’s hidden photographs have all the movement of the street: women pass by, sometimes slightly blurred, their skirts swaying, and men doff their hats to the face above the unseen, but all-seeing, lens. Each photo is circular, reminiscent of a spyhole, and just as furtive.

Paul Martin, who captured the moody, rain-slicked streets of London by gaslight, also secretly photographed London streets using his detective camera. It was disguised as a brown paper parcel, as though it was “one or two books of the same size neatly wrapped up by a shopkeeper,” according to a review of the camera. To protect it from rain, Martin decided to give it a black leather case along with a few other modifications, and went out into London’s streets. “It is impossible to describe the thrill which taking the first snaps without being noticed gave one, and the relief at not being followed about by urchins, who just as one is going to take a photograph stand right in front shouting, “Take me, guv’nor!,” he later recalled.

Martin’s goal was to show something new—not the aesthetic of “careful composition, superimposed clouds, soft printing” but, rather, “people and things as the man in the street sees them.” His photos are about as close as we can get to a sensory slice of Victorian London. In one photo, a Billingsgate market fishmonger walks casually across cobblestones with a tall basket balanced on his head. Another photo shows a traffic accident on High Holborn, where a policeman helps a passenger down from a tipped-over hansom cab. “The first thing to do in such a case,” Martin recalled in his 1939 book, “is to sit on the horse’s head.” Martin captured more: street vendors, a knife grinder, a fair in Battersea Park, a crowd waiting for a policeman’s funeral, and yes, “urchins,” three barefoot children sitting on a street curb. In Martin’s photos, London street life—messy, unfiltered, vibrant—does not so much cry out as roars. It demands to be seen as a record of the ordinary yet extraordinary activities of people who once lived.

He also photographed public holiday festivities in Hampstead Heath with a Kodak provided to him by the Eastman company, although he preferred his own detective camera. (Eastman Kodak also offered Martin a job that he turned down, a decision he later regretted.) Martin took his camera outside of London, where he photographed beach scenes and seaside activities: children watching a Punch and Judy show; a crowd behind a barrier, listening to a concert. Martin also surreptitiously snapped couples canoodling in the sand, and women tentatively stepping into shallow, foaming water, their long skirts raised and billowing at mid-calf.

Had Martin been caught taking photos of women at the beach, he might have faced some retribution. In articles and letters in both British and American photographic journals, many lamented the camera fiend’s activities and suggested various forms of punishment, particularly if the fiend was caught photographing women at the beach. They ranged from demanding that the photographer hand over negatives, to destroying the camera (with a brick, suggested one reader helpfully), to a “good horse whipping” of the fiend.

Regardless of the near-universal hatred of the camera fiend, the attitude of the amateur photographer journals ranged from oblivious to obliging. In 1893, for example, The Amateur Photographer encouraged its readers to go to Brighton Beach to photograph “fat men” for some “funny plates, or some laughter-moving lantern-slides.” Some years earlier, the same journal had expressed regret that no one had photographed the actress Sarah Bernhardt falling down some stairs. Upon learning that some readers were deterred from entering competitions because their names would be published, the editors readily suggested pseudonyms. Eventually, The Amateur Photographer did publish guidelines for photographic etiquette, which included not using a camera “for a thunderingly good practical joke.”

In the 1890s—as amateur photography and its devious brigade of camera fiends boomed—newspapers and magazines began to reproduce photographs in print using the halftone process. Candid snaps of well-known figures soon became photographic fodder. In 1899, The Penny Pictorial Magazine started a feature called “Taken Unawares: Snaps of Celebrities Taken Without Their Knowledge,” essentially a nineteenth-century precursor to the twenty-first century’s “stars without makeup” magazine editions. The August issue published the photograph of Queen Victoria smiling, the Belgian king standing awkwardly by the sea at Ostend, and the German emperor meeting some clerics. The page invited contributions from photographers to be sent to the “Snapshot Editor.” Similarly, in 1910 The Graphic published “Unconventional Portraits of Celebrities,” in which it praised the “snapshottist” who supplies a “constant round of pictures of the great taken unawares.”

One place seemingly safe from a prying camera on the hunt for news was an English courtroom. But in October 1908, a press photographer named Arthur Barrett entered Bow Street Magistrates’ Court with a camera squirreled away in his top hat. He’d cut a small hole for the lens and, once inside the courtroom, he placed the hat on a ledge and directed it toward the three highly newsworthy defendants in the dock. He later recalled how he coughed to hide the sound of the exposure, as he captured the faces of the alleged criminals Emmeline Pankhurst, her daughter Christabel Pankhurst, and Flora Drummond.

The three suffragists had been arrested for conduct likely to breach the peace after encouraging the public to “rush,” or invade, the House of Commons at the opening session of Parliament. Christabel Pankhurst acted as the defense attorney. (Despite having a law degree from the University of Manchester, as a woman she could not practice law professionally.) The interest in the trial was such that “a stranger passing the police court earlier in the day might have mistaken it for a theatre at which a matinée performance was to be given, so large was the number of women waiting for the opening of the doors,” reported The Daily Mirror.

Despite Christabel’s questioning of Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George and Home Secretary Herbert Gladstone, whom she had audaciously called as witnesses, and her two-hour closing argument, the judge issued an order against the defendants. When they refused the order—to pay a fine and keep the peace for twelve months—the judge sentenced the three women to Holloway Prison (Christabel for ten weeks, Emmeline Pankhurst and Drummond for three months). As they left the dock, The Times of London reported, “a cheer was raised in the crowded Court” with “hysterical shouting and the waving of handkerchiefs.” Amid the ruckus, Emmeline Pankhurst shouted, “I congratulate the Government on having another servant who does what he is told to do.”

Barrett’s photographs were a coup. Pictures of the suffragists in the dock ran in The Daily Mirror, The Daily News, and the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, and one was also reproduced as an illustration in Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper accompanied by the hysterical headline “Suffragette Attack on Parliament.” The press coverage of the trial was described by one suffragist as a “suffrage meeting attended by millions.” It was a scoop for Barrett; it was also not the last time he would photograph suffragists without their knowledge.

By this point, anyone who was arrested in England and Wales had to have their photograph taken, a requirement that had been in place since the 1871 Prevention of Crimes Act. But not all prisoners complied, including the suffragists, who strongly resisted any attempts to get a clear photograph of their faces. One example is a photo of suffragist Evelyn Manesta, who was photographed at Strangeways Prison in Manchester with her eyes tightly shut and her lips pressed together. She was in prison after using a hammer to smash the glass on thirteen artworks at the Manchester Art Gallery in early April 1913, along with two other suffragists. In his sentencing, the judge made it clear he would prefer a harsher publishment, stating, “If the law allowed me I would send you round the world in a sailing ship.”

Except that there are two versions of Manesta’s photograph. In one, she wears a scarf and is shown against a blank background. In another, the original version, she is pictured in what looks like a prison doorway. The scarf is partially covered by an arm—the arm of the prison warden who was restraining her around her neck. The prison governor evidently realized that circulating a photo that depicted violence against a suffragist prisoner was unwise. “The photographer informs me that he can easily print out the matron’s arm around Manesta’s neck, should it be considered desirable to do so,” he wrote, after the photo was taken, adding that it was “required in order to prevent her holding her head down.” Only the manipulated version was circulated.

In that same month, April 1913, Parliament passed what was known as the “Cat and Mouse” Act, officially titled the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act. Under this new law, an imprisoned suffragist whose health was in danger from a hunger strike could be released from prison, and rearrested once she recovered—provided she could be identified. (Manesta was released from prison early under the Cat and Mouse Act; The Suffragette reported that she was “in a state of collapse, after a forty-eight hours hunger-strike.”) So on April 26, the order came from the Home Office to photograph and fingerprint all suffragist prisoners without fail. “As, however, photographs cannot be taken by force, you should, if the prisoner resists or is thought to be likely to resist, communicate by letter or telephone with the Special Branch, New Scotland Yard, when an expert photographer would be sent to the Prison and would endeavour to take a photograph without the prisoner’s knowledge.” The expert photographer in the form of Arthur Barrett was now taking surveillance photographs of suffragists in the yard at Holloway Prison. (Fingerprints, the same document noted, should be taken “in every case,” and by force “if necessary.”)

Barrett attempted some photographs from what we’d now consider a classic stakeout position, snapping clandestine photos from inside a van. But he struggled to focus the lens on his subjects from such a distance. The police were perhaps also not as subtle as they had hoped. At the end of May 1913, The Suffragette reported that imprisoned suffragists had been taken outside to exercise one by one, not as a group; and after being led by a prison warden to a particular area, they described hearing a “click” and seeing a camera hidden behind a metal gate. The article noted, with some satisfaction, “evidently the Government is finding the enforcing of the Cat and Mouse Bill a difficult task.”

The police were also concerned about the expense of maintaining a freelance photographer, so in August 1913, New Scotland Yard purchased an eleven-inch telecentric Ross lens, an early version of a telephoto lens. Testimonials from photographers around this time praised the lens as being especially useful for sports photography, news photography, and for photographing wild animals such as birds and big game. When photographing captive animals, wrote one, the lens offered a “decided advantage from a point of personal safety while making exposures of savage and bad-tempered animals.” Another photographer, after using it during the previous year’s Olympic Games, called the long lens “absolutely epoch-making.” But now, long lenses were being used for a new and much more sinister kind of sport, surveillance photography, in which the British government had become a leading player.

Such was the covert nature of the photo operation that the Home Office designated code names for its telephone conversations with Barrett and Holloway Prison. The suffragists were code-named Wild Cats; Barrett was Banjo. Secret communications were also part of the suffragists’ operations. The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), founded by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, had, by this point, developed code names to use in secret messages. Individual cabinet members were code-named after plants: Lloyd George and Gladstone were known as Nettles and Thorns.

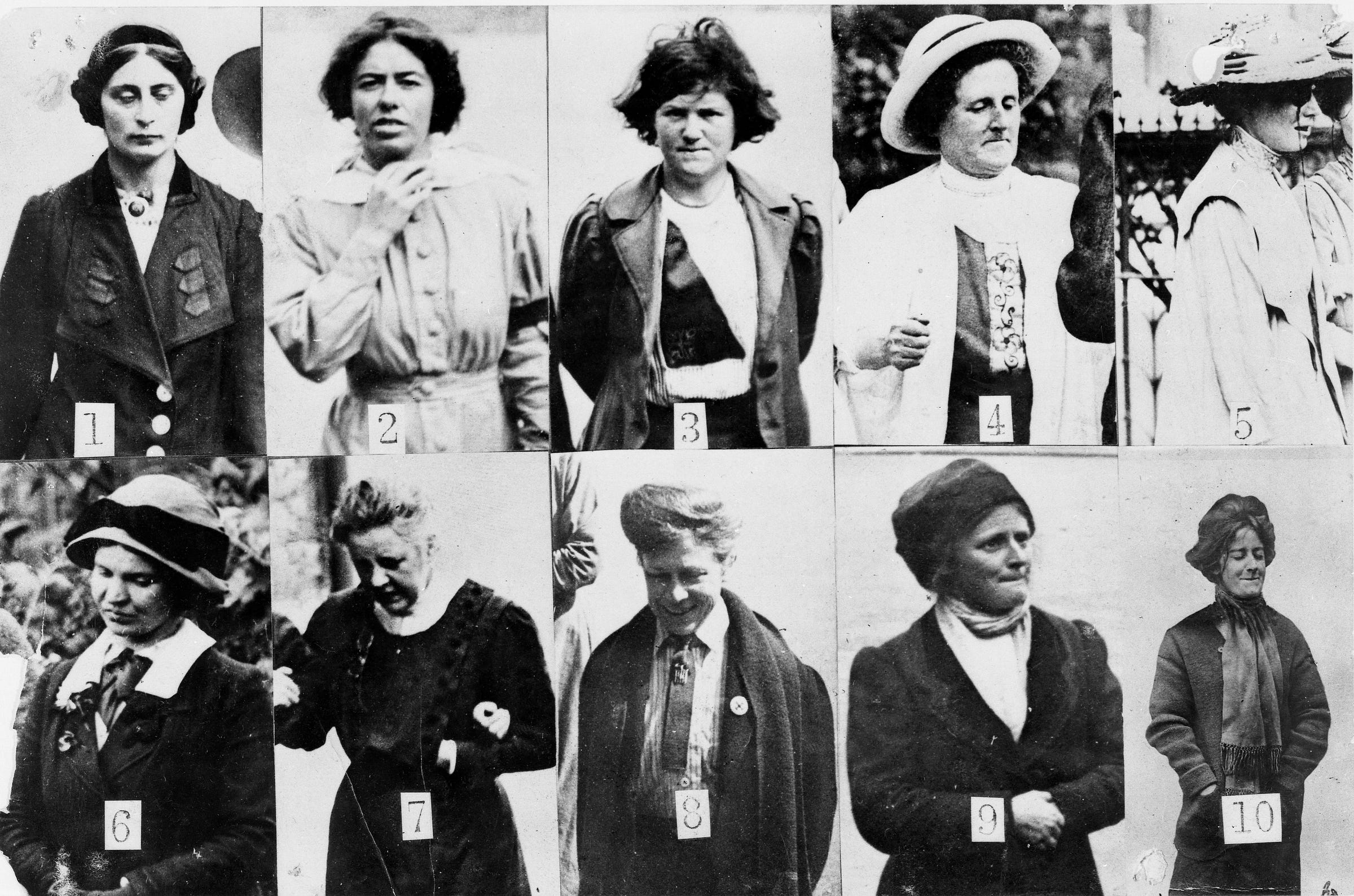

The following year, on March 10, 1914, Mary Richardson entered London’s National Gallery with a butcher’s knife and slashed Diego Velázquez’s painting The Toilet of Venus, also known as the Rokeby Venus. After Richardson’s attack, the National Gallery closed for two weeks; the British Museum stayed open but permitted women to enter only if they had a letter of recommendation from, or were accompanied by, a man. The Home Office then released its mugshots of suffragists to galleries. One set, still held by the National Portrait Gallery and attributed to the Criminal Record Office, shows ten suffragists, some of whom are clearly being seen through the end of a long lens. In the bottom right corner is the manipulated image of Evelyn Manesta.

In 2003, one hundred years after the WSPU was founded, the suffragist surveillance photographs were included in the exhibition “The March of the Women: Suffragettes and the State 1906–1918,” at the National Archives in London. Up until this point, the surveillance records had not been widely seen, and the press reaction to the exhibition conveyed a deep unease at what the archives had revealed. Looking at these photos now, the feeling remains. As historian Jill Liddington has noted, it was evidence of how the British government “secretly spied on women imprisoned merely for demanding the basic democratic right to vote.”

Barrett, for his part, went on to join the Royal Naval Air Service as an aerial photographer during World War One. But his involvement with the suffrage movement hadn’t quite ended. In 1955, Barrett joined a reunion of British suffragists and brought with him his top hat and secret camera. He showed some of the suffragists how it worked, which was captured on a British Pathé newsreel, available on YouTube.

The hand camera, in all its guises, changed photography. It changed what people photographed, and how they photographed it. It brought out some photographers’ worst instincts; for others, it created a crucial record of everyday life. The candid shots it produced marked the start of long-running debates about privacy and consent, and precipitated sleazy paparazzi shots and silent surveillance images. The hand camera truly was, in the words of one Kodak advertisement, “the camera that takes the world!”

Excerpted from Flashes of Brilliance: The Genius of Early Photography and How It Transformed Art, Science, and History. Text by Anika Burgess © 2025 W. W. Norton and Reprinted with permission.

About the author

Anika Burgess is a writer and photo editor. She has been published in The New York Times and Atlas Obscura, and her short humor has been featured in The New Yorker. Anika holds degrees in law and history from the University of Sydney and qualified as a lawyer before transitioning to a career in journalism. Anika lives in New York with her husband, son, and an obstinate schnauzer called Sigmund.

You can follow what she’s up to on Instagram @aburgessphoto.

Submission is easy: Tell me why you want this book!

You can reply to this newsletter, email me at flakphoto@gmail.com, comment below, or drop me a line on my Instagram post by clicking here:

Just tell me why you’d like to add Flashes of Brilliance to your collection.

I’ll draw two random winners from the replies on Monday, October 13, 2025.

That’s it! Thanks again for reading, folks, and for supporting my work. I’m looking forward to hearing from you!

This was a fascinating read and still current...the birth of the paparazzi, the fight for women's rights still going on in parts of the world. I found that Pathe News report on the suffragette's reunion here https://youtu.be/fyImzmaypJ8?si=6CgPl2IR4RPLZPRa ... Barratts hat-cam is brilliant!

What a fun essay! This quote cracked me up right out of the gate 😂 . One journal described the fiend as someone who “delights in portraying his acquaintances in all sorts of ridiculous situations.”