Revisiting The Jazz Loft Project

Sam Stephenson shares an excerpt from his latest book, a reissue of an acclaimed collection of images from photographer W. Eugene Smith’s time in a New York City loft among jazz musicians.

My twin passions — jazz and photography!

Something different this week: An extended essay excerpt from a good friend of FlakPhoto, the writer Sam Stephenson. This is a lengthy post, so I’ll set the stage with a recording so you don’t have to spend too much time scrolling before getting to the goods:

Sam is an incredible writer and probably one of America’s foremost experts on photographer Eugene Smith. I’m excited to host Sam in Madison this weekend. He’s speaking at the Wisconsin Book Festival on Saturday, October 21 at 4:30 p.m.

You can read more about Sam’s talk on the WBF website, and if you use Facebook, you can RSVP for our event. Thanks also to the good folks at the Arts + Literature Laboratory for hosting Sam’s talk at their downtown art space and to PhotoMidwest for partnering with me on this project. Please join us if you’re in town.

I’m excited to share Sam’s work with you today and hope you like it. As always, let me know what you think. Please leave me a comment or reply to this email to write me directly. Enjoy!

“See, actually, I’m doing a book about this building itself…Out the window and within the building because it’s quite a weird, interesting story.” — W. Eugene Smith, recorded on his loft tapes, ca. 1960

In the heart of New York City's wholesale flower district sits 821 Sixth Avenue, a nondescript five-floor loft walkup. It was built in 1853 for commercial purposes by someone named George E. Hencken. Today, the narrow building is slightly wider than the length of the parking space in front of it. Its bricks are painted gray and layered with decades of accumulated scum and grime. High-rise condo towers, which have sprouted since the neighborhood was re-zoned residential in the late 1990s, loom over the building. In a matter of time, 821 Sixth Avenue will be sold and demolished to make way for more condos. Meanwhile, the Chinese-American owners, the Chang family, import and sell wigs there, very successfully. They bought the building in 2002 from Bernie's Discount Center, which sold televisions, microwave ovens, air conditioners, and other appliances in the space for four decades. It is an unprepossessing place, bearing no clues of the crossroads of jazz, art, and post-War urban American lore that it used to be. The Chang family never heard about it.

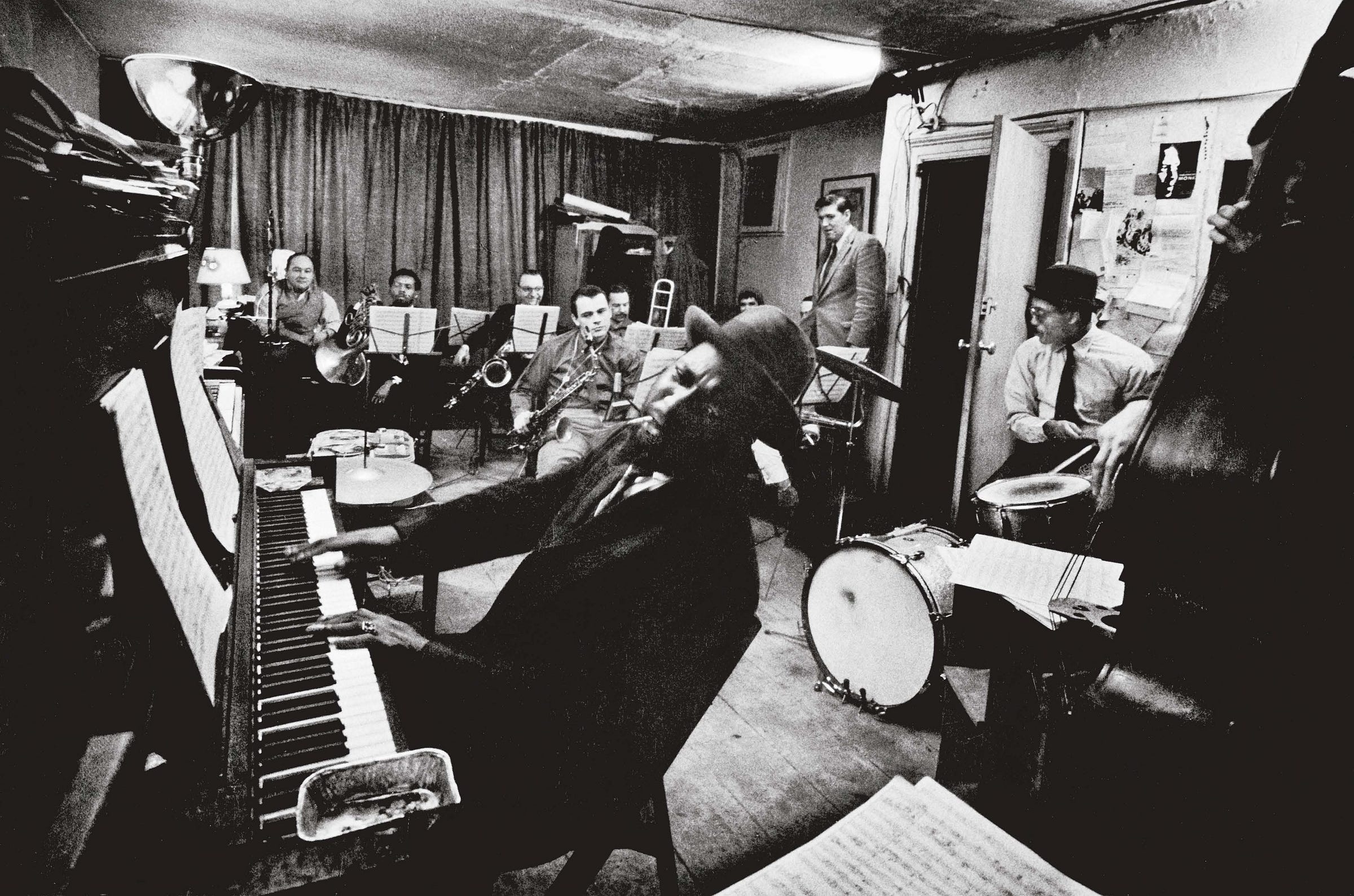

For ten years, beginning in 1954, jazz musicians by the hundreds climbed the creaky, mildewed wooden stairs for sessions – both impromptu and formal — in the middle of the night. Many of the biggest names in jazz hung their hats there, for at least a few hours, if not for several years. Thelonious Monk and Hall Overton rehearsed the music for Monk’s legendary big band concerts at Town Hall in 1959, at Lincoln Center in 1963, and at Carnegie Hall in 1964. Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, and Teddy Charles honed the sound heard on the record “Blue Moods” there. The place drew such prime players as Bill Evans, Roland Kirk, Zoot Sims, Jimmy Giuffre, Roy Haynes, Sonny Clark, Stan Getz, Jim Hall, Don Cherry, and Paul Bley, who formed ad hoc ensembles that often included veteran stars like Buck Clayton, Vic Dickenson, and Pee Wee Russell. Ornette Coleman went there to play the beat-up, idiosyncratic Steinway B piano on the fifth floor by himself. Alice Coltrane and Joe Henderson rented rooms on the fifth floor for a few months after moving to New York from Detroit in 1961. Musicians from other genres frequented the place, too; minimalist composer Steve Reich and conductor Dennis Russell Davies, and folk singer Nehama Hendel. Photographers Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, and Henri Cartier-Bresson went there, and painter Salvador Dali and writers Anais Nin and Norman Mailer.

For every renowned musician who visited 821 Sixth Avenue, however, there were dozens of obscure ones. Strangers — unproven newcomers — wandered into the place: if you could play an instrument, you were okay. A fifteen-year-old pianist Jane Getz came in from Texas, pianist Dave Frishberg from Minnesota, and bassist Jimmy Stevenson from Michigan. But this was no romantic oasis of “cool” acceptance and warm fellow-feeling. If you couldn’t play—if you weren’t good enough—there was no reason for you to be there, unless you had other assets. There was dope to be smoked, and sometimes heroin or methedrine to shoot up, and every once in a while, there was sex to be had. The door facing the sidewalk could be unlocked or completely missing – a cave or mine shaft in the dead center of Manhattan - and junkies snuck in, climbed the stairs, and stole things to pawn. Roaches and mice and rats and stray cats loved the place, too.

During the daytime, the smell of flowers wafted through the neighborhood and the open windows of the loft building. Growers from Long Island began ferrying and carting their flowers to the intersection of Sixth Avenue and Twenty-Eighth Street sometime around the Civil War. Before refrigeration, perishable merchandise required a central distribution point, and this corner was perfect for burgeoning Manhattan. The same location was also good for vice. The flower shops closed down late in the afternoon, and the Sixth Avenue elevated train canopied the street. Before World War I, the neighborhood was known as the “Tenderloin,” the primary red light district in New York. The notorious dance hall, the Haymarket, was at Sixth Avenue and 30 Street, and the upper floors of many of the flower shops turned into brothels or gambling joints after dark. Artist John Sloan documented the seedy scene with numerous paintings and drawings.

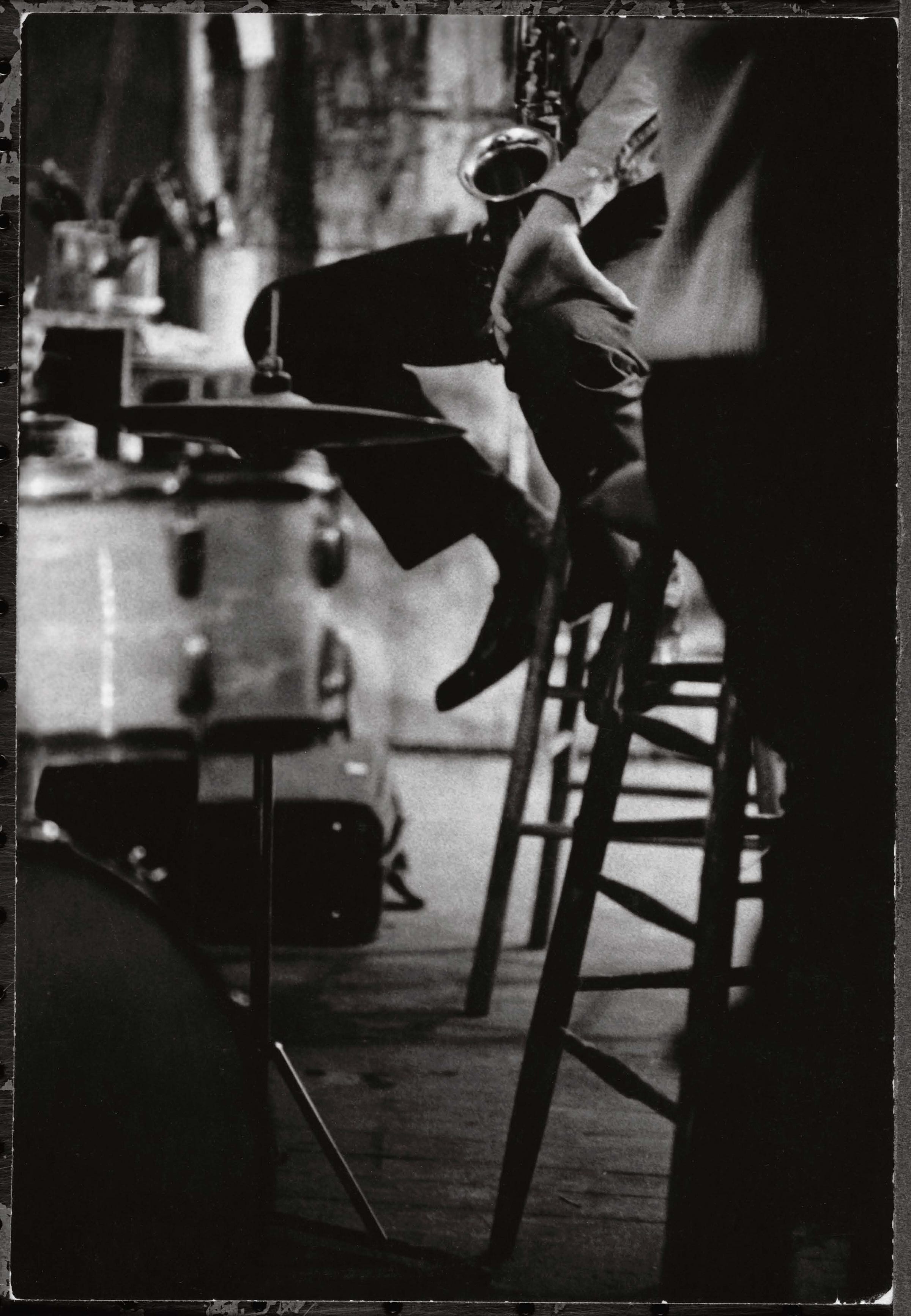

Sex, gambling, and flowers – fleeting products; it made sense for them to find a home here. A few decades later, the real estate cheapened by its legacy and affordable for artists, the flower district was the place to hear some of the best after hours jazz in New York City. The unorthodox rhythms of the music meshed with the daily patterns on the street. At dawn, the flower growers would arrive to peddle their blooms in the neighborhood markets as musicians were stumbling out of the building. Then, after midnight, with the shops closed and quiet again, the jazzmen (and a few women) resurfaced for a night of full-tilt blowing.

W. Eugene Smith moved into the building in 1957, a period in his life that he later called "the worst" — a relative term, given his always stormy affairs. The scene anchored and inspired him. It was an intersection of people that could have occurred nowhere other than New York. Jazz musicians were flocking there from all over the country, along with many others aspiring for new lives. Suddenly this building, which had been abandoned for decades, became a spot where you could stop by and see an icon, or unknown junkies strung out on the fourth floor landing, or see nobody at all, only empty Rheingold bottles, hundreds of cigarette butts, and tin cans of half-eaten food. Some nights, from the sidewalk, you’d hear transporting saxophone solos coming out of the fourth or fifth floor windows. Other nights, the only sound would be the periodic throttle of the Sixth Avenue bus, which had a stop at the corner of Twenty-Eighth Street.

Somewhere floating on the premises, or peering out his fourth floor window, the furtive Smith and his camera clicked away. In a November 1958 letter to his friend Ansel Adams, Smith wrote: “The loft is a curious place, pinned with the notes and proof prints…with reminders…with demands. Always there is the window. It forever seduces me away from my work in this cold water flat. I breathe and smile and quicken and languish in appreciation of it, the proscenium arch with me on the third stage, looking it down and up and bent along the sides and the whole audience in performance down before me, an ever-changing pandemonium of delicate details and habitual rhythms.”

The last phrase well describes the loft music, too, which Smith recorded from the recorder in his fourth floor darkroom. He had wires reaching like roots through walls and floors to microphones all over the place. He once called the story of the loft scene a "unique piece of Americana." From his photos and tapes and from interviews with participants, we can document 597 people (and counting — as of this writing) who passed through the dank stairwell of this building in the 1950s and 1960s. The true number could be twice as high. From all walks of life all over the map, only a dozen or two of these people went to college. What building in 21st century America — that is not an enterprise or institution — has this kind of diverse traffic? Is there one? Anywhere?

A Congenial Haunt — Word Gets Around

After the Sixth Avenue elevated train tracks were razed in 1939, Lewis Mumford wrote in The New Yorker, "The dreary mess of buildings that loitered beside the old 'L' — much of it dating back to the 1870s — has long been ready for demolition." In 1954, when David X. Young, a twenty-three-year-old artist from Boston, first saw 821 Sixth Avenue, it still was a dreary mess. Young needed a large, low-rent place in which to paint. Through his friend, Henry Rothman, an artist who ran a frame shop on 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue, Young found a space in 821 Sixth Avenue along with musicians Hall Overton and Dick Cary. They each paid $40 per month to landlord Al Esformes, who had a check cashing business across the street. Young took the fifth floor, Overton the fourth, and Cary the third. Soon, photographer Harold Feinstein and his wife, pianist Dorrie Glenn, took over half of Overton’s space on the fourth floor.

"The place was desolate, really awful," said Young, who later lived in a loft on Manhattan's Canal Street for four decades before dying in 2001. "The buildings on both sides were vacant. There were mice, rats, and cockroaches all over the place. You had to keep cats around to help fend them off. Conditions were beyond miserable. No plumbing, no heat, no toilet, no electricity, no nothing. My grandfather loaned me three hundred dollars and showed me how to wire and pipe the place."

As a teenager, Young developed a passion for jazz. He was a regular at Boston jazz clubs like the Savoy and the Hi Hat, and he made friends with many musicians. The improvisational energy of jazz inspired his abstract expressionist paintings. When he moved to New York, Young helped to pay his bills by designing jazz album covers for Prestige Records. He did covers for Jimmy Raney, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Teddy Charles, and Art Farmer. Privy to many recording sessions, Young found himself hanging out with musicians.

"One of the problems they always had," Young said of the musicians, "was finding places to rehearse where they wouldn't bother anybody with noise. I went with Bob Brookmeyer and Jimmy Raney to some of their practice sessions at Nola's studio, where everybody would chip in fifty cents or something for a room. But that wasn't good. A lot of them didn't have any money, and there'd be a time limit on the rental. So I thought about my loft. I realized I had the ideal space for these sessions. I checked around and found a good piano for fifty dollars, delivered. Some movers, huge guys, brought the piano over to my loft, hoisted it with ropes up this side of the building, and brought it in through my front window. I got Billy Rubenstein to come over and tune it, and we were in business."

Cary also brought a Steinway B piano into his third floor loft, and Overton moved two upright pianos into the fourth floor. Cary and Overton were both married, with permanent residences in the city. They rented their loft spaces for practice sessions, but they frequently stayed overnight. Cary worked as a pianist, arranger, and a horn player in Dixieland- and New Orleans-style bands, including a few with Louis Armstrong. In Young's mind, he was the ideal tenant. "Cary couldn't have cared less about the terrible conditions," Young said. "His way of dealing with the mice and cockroaches was to set up little plates of food in the corners. He said if you fed them, they wouldn't bother your real food."

Overton was a dashing, six-foot-four suit-and-tie man who on first glance, seemed out of place in the squalor of 821 Sixth Avenue. After carrying stretchers in combat in France and Belgium in World War II, he taught classical composition at Juilliard and, later, at Yale and the New School for Social Research. His wife, Nancy Swain Overton, was a successful singer, first in a group called the Heathertones and later in the iconic Chordettes of “Mister Sand Man” fame, and they shared a nice house in Forest Hills with their two young sons. Overton was revered and beloved as an innovative teacher and arranger. He had a knack for finding and nurturing the unique qualities inside all of his students, rather than imprinting his methods on everyone. He worked with Charles Mingus, Oscar Pettiford, Teddy Charles, and Stan Getz, and forged a longstanding relationship based on deep mutual respect with Thelonious Monk — not an easy task. Minimalist groundbreaker Steve Reich studied with Overton in the loft once a week for two years in the late 1950s, an experience he calls pivotal to his career. From Monk to Reich, the sweep of Overton’s behind-the-scenes influence may be unsurpassed in American music history. But he seemed to care nothing about acknowledgement. He preferred the obscurity of his studio loft to the hallowed halls of Juilliard.

At night and on weekends, Overton gave lessons to a range of folks like the billionaire tobacco heiress Doris Duke, Marian McPartland, seminal conductor Dennis Russell Davies, and composer Carman Moore. Jazz legends would stop by without an appointment and pick Overton’s brain and soul, friendship and camaraderie the medium of exchange. His substantial, yet unassuming presence at 821 Sixth Avenue was critical to the scene.

His friend, photographer Robert Frank, remembers him fondly today, “He was an astonishing man, his passion and his belief in whatever he would do. Since then, I haven’t met anyone that comes near that passion and belief in what he does and what it should do, and the effect of his work. He believed it would change the world, and nobody today of the younger people think like that. I haven’t met them.”

Word spread in the jazz underground that 821 Sixth Avenue was a congenial haunt. "We were always looking for spacious places to play late at night," the bassist Bill Crow says, "especially places with tuned pianos. This place was perfect." The location in the center of Manhattan made it easy for people to drop by on their way to and from somewhere else. It drew both established stars and young players eager to prove themselves on one or another of the upper three floors. "Charlie Mingus and I started going [to the loft] a lot in 1954 and 1955," Teddy Charles says. "We had some wild, free sessions over there: Art Blakey, Miles Davis, Art Farmer, Gigi Gryce, Mal Waldron, Jimmy Knepper, Oscar Pettiford, and dozens of other guys. I remember Bill Evans coming into the loft sometime around 1955 or '56. He looked like a school kid. But within a few months or a year, he'd taken the whole city by storm. Nobody knew who the hell he was when he first came in there." Pianists Paul Bley and Freddie Redd remember seeing Charlie Parker in the loft sometime before he died in March of 1955.

The saxophonist Leroy "Sam" Parkins remembers New Year's Eve in 1959 when he was playing with the drummer Louis Hayes, the bassist Doug Watkins, the saxophonist Zoot Sims, the guitarist Jimmy Raney, and the pianist Sonny Clark. "We were playing and having a good time," Parkins says. "Then the door flew open, and Lee Morgan, Pepper Adams, and Yusef Lateef walked in. The whole scene changed immediately, and the music reached an unreal level. The sessions didn't gel every night, but this time the damn place nearly exploded."

Bill Takas was one of the regular bass players; he and Sonny Clark and the drummer Ronnie Free made up the rhythm section for many sessions. "Because basses, pianos, and drums are so much harder to move, any place with a rhythm section would attract horn players from all over town," Takas says. "We'd put the word out and you never knew how many would show up — two, three, or twenty-five horn players. The masters might be there, or cats you'd never seen before.”

In 1960 Dick Cary and David Young moved out, and a series of young musicians moved in: drummer Gary Hawkins, bassist Hal Bigler, drummer Tommy Wayburn, bassist Dave Sibley, and drummer Frank Amoss. In 1961 a young bassist from Detroit, Jimmy Stevenson, and his wife Sandy took over the fifth floor from Amoss, and the scene began to change. Free-jazz players such as Ornette Coleman, Alice McLeod (Coltrane), Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Roswell Rudd, Joe Henderson, Chick Corea, Joe Farrell, Henry Grimes, Roland Kirk, Paul Plummer, Albert Ayler, and Steve Swallow joined the fray. Their penchant for less structure, fewer stated chords, and soloing without limits altered things. The common musical repertoire fragmented somewhat. But the camaraderie held up to a remarkable degree. The noncommercial atmosphere of the loft and the acceptance of strangers was a break from clubs and studios, which preferred established stars. Ronnie Free, for example, is credited by many with having propelled some of the loft's greatest sessions ("Sometimes it was like he was burning, he was so hot," the bassist Steve Swallow says), but his name registers hardly a trace in official jazz histories today.

The pianist and composer Dave Frishberg, who discovered 821 soon after leaving the Air Force in 1957, found it liberating to be ''playing in a free atmosphere all night long without anybody complaining or hearing you except the guys you were playing with." But, he adds, "It wasn't pressure-free. If you didn't play well, you'd hear about it." And even though mice were running around the floor, a social etiquette prevailed. "It was generally understood," Swallow says, "that you could drop by any night after eleven o'clock. It was considered rude to show up earlier."

“There was more than one loft. There were several in the area. But this was a main one, where Jimmy Stevenson lived,” says baritone saxophonist Ronnie Cuber. “Guys like Joe Farrell and Chick Corea used to go jam there. Henry Grimes, Gil Coggins, and Lin Halliday, and Walter Davis, Jr., and Vinnie Ruggierio and Nico Bunink. Guys coming in from everywhere. Joe Henderson. He came in from Detroit. Guys like Blue Mitchell, you know. Elmo Hope. I remember Danny Richmond being up there.”

Regulars debate how much the loft's relaxed attitudes toward drinking and drugs attracted musicians and scenesters. Marijuana and alcohol had long been staples in the jazz diet, and both were freely available at the loft, as were, occasionally, heroin, peyote, and methamphetamines. A go-all-night lifestyle doesn't encourage normal eating and sleeping habits. Swallow remembers one session in particular: "Zoot Sims was drinking and playing his ass off, as he always did. He kept a coffee can nearby and spit blood into it all night. He had an incredible constitution.” Swallow — who had left Yale University at age eighteen, in 1958, to play jazz full-time in New York — often jammed into the early hours with Sonny Clark, who, unbeknownst to Swallow at the time, was a serious drug abuser. "Sonny would hit me up for loans, and I'd give him a buck or two. I didn't know the junkies hit up the younger guys because the older ones were tired of loaning them money. I was naive. But to me, shelling out a couple of bucks to Sonny Clark was like paying tuition. He taught me a lot about music that I could not have learned anywhere else.”

In the summer of 1961, Clark strung out on heroin, collapsed in the loft, and his heart stopped beating. A sixteen-year-old girl from Delaware by way of Chicago and Cincinnati, Virginia McEwan, saved Clark with amateur CPR. She and her boyfriend, saxophonist Lin Halliday, had been squatting in the loft stairwell since May of that year. In saving Clark, McEwan also saved the building from the heat of the police. She also allowed Clark to live for another eighteen months, a period in which he recorded several classic albums on the Blue Note label before he suffered an overdose and died while playing at Junior’s Bar in the Alvin Hotel on 52nd and Broadway. Today, McEwan lives in Port Townsend, Washington, with her husband, bassist Ted Wald, whom she originally met in 821 Sixth Avenue.

The Red-Hot Eugene Smith

In 1957, Smith moved into the space on the fourth floor next to Hall Overton. The space was previously occupied by Smith’s longtime friend and assistant, photographer Harold Feinstein. A legendary photojournalist since he photographed combat in World War II in his early twenties, Smith was thirty-eight years old and at the top of his profession. But he was suffering through a harrowing stretch in his personal life. His misery made many of those closest to him miserable in turn. He had four children and a wife living at his home in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, and another child living with a lover in Philadelphia. He virtually abandoned all of them when he moved into 821. He had been desperately trying to complete the most ambitious project of his life: a kaleidoscopic study of the city of Pittsburgh.

Smith had quit a stable, high-paying position with LIFE in early 1955 and had gone to Pittsburgh for a seemingly routine three-week freelance assignment. His assignment was to make one hundred scripted photographs for a book commemorating the city's bicentennial. He stayed for a year and made some twenty-two thousand photographs of the city. Aided by two successive Guggenheim grants, Smith spent three more years making prints and devising layouts of an essay he compared to Beethoven’s late string quartets, Joyce’s Ulysses, and the plays of Williams, O’Neill, and O’Casey. He said two thousand negatives were valid for his essay, and he had them pinned up in 5x7 inch work print form all over the loft’s walls, up and down the stairwell. He eventually brought more than six hundred of the images to a master print form, roughly 11x14 inches in size. It was a herculean accomplishment. But it fell short of completion, an unfinished symphony. His magnum opus may have existed on the walls of 821 Sixth Avenue — 5x7s pinned up in rhapsodic sequences — but a public presentation would be impossible.

LIFE and Look magazines each offered Smith $20,000 ($154,000 in 2009 dollars) for the rights to the Pittsburgh prints, but the magazines would not agree to his demands for editorial control, and Smith rejected their offers, despite his family’s nearly desperate financial situation. He never finished the Pittsburgh project. It was, he said in a letter to his friend Ansel Adams, an “embarrassment” and "debacle.”

The loft at 821 Sixth Avenue became Smith's refuge during these years of escalating desires and diminishing results. His financial problems mounted, and his manic highs and suicidal lows were aggravated or produced — it was hard to say which — by addictions to alcohol and amphetamines. But Smith never stopped working. In a 1976 interview, he recalled the time around 1958 at his peak as a photographer but his nadir as a human being: "My imagination and my seeing were both — I don't know if I can think of the right term — red hot or something. Everywhere I looked, every time I thought, it seemed to me it left me with a great exuberance and just a truer quality of seeing. But it was the most miserable time of my life.”

Smith’s documentary goals in the loft were a departure from his previous journalistic work. He made his name photographing combat in the Pacific theater of World War II; a physician in rural Colorado (“Country Doctor,” 1948); an African-American nurse midwife in poverty-stricken South Carolina (“Nurse Midwife,” 1951”); and a peasant village in Spain, (“Spanish Village,” 1951). In each case, he went out into the world and returned with powerful, sensitive images. Then he fought bitterly with LIFE’s editors for control of the work. Each published essay was preceded by threats to quit, even threats of suicide. It was unbearable for both sides. Then, after publication, LIFE’s enormous readership would weigh in — coffee tables, waiting rooms, barber shops all over America — and everything would be okay. At LIFE, Smith had created a legend for himself: compassionate photographer as indomitable hero.

In the loft, Smith was devastated and depleted by the unfinished Pittsburgh project. Nobody would hire him for fear of triggering another quixotic odyssey. He had no assignments to document the outside world. So he turned his documentary fevers to the space and time right around him, 821 Sixth Avenue and the flower district neighborhood. Says his friend, photographer Robert Frank: “Gene went from a public journalist to a private artist in the loft. I’m sure the intensity was still the same, but there weren’t the goals of changing the world with this body of work, at least not like before.”

The musicians who visited the loft — staying up all night, tuning out the workaday world, driven by passion or pathologies rather than cash or fame — inspired Smith and provided focus for his energy. He loved music. On the front lines of World War II, he had amazed soldiers by carrying boxes of records and a portable phonograph to the front lines. When he died in 1978, he had only eighteen dollars in the bank, but he owned more than twenty five thousand vinyl records, mostly classical and jazz. He especially admired music that revealed beauty in dissonance — late Beethoven, Bartok, and Thelonious Monk were favorites — and he wanted his photography, especially his Pittsburgh project, to achieve that same rarefied state.

Smith left evidence of himself in stacks of prints all over 821, even if he was not always visible in person. Zoot Sims affectionately nicknamed him "Lamont Cranston," after the character in the radio serial The Shadow (“Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!”). Musicians sensed that Smith was a comrade, a fellow outcast.

The image of Smith maintained by the loft musicians contrasts with the one that still prevails today in many photography circles, where his compulsions are judged to have been driven by megalomania and lunacy. Freddie Redd says, “Gene Smith is just a sweet memory. He was this quiet person who was, you know, just nice to be around. He always had his cameras around his neck. He never bothered anybody.”

The guitarist Jim Hall remembers a night when he and Jimmy Raney had a gig at the Village Vanguard jazz club. Their wives attended and took snapshots of the band. When Hall and Raney made their late-night rounds at 821 Sixth Avenue, they asked Smith to help with their film. "We were a bit uncomfortable asking the Master to help us with our piddly photographic work," Hall says, "but he responded with kindness and generosity. He took us into his darkroom and treated our film like it was his. You'd have thought he was making pictures for LIFE. He was extremely particular about it. That's how he always was.”

Ronnie Free, the tireless drummer said to have propelled many of the loft's best jam sessions, says he has "no memories of Gene sitting down," and adds, "I have no memories of him eating or sleeping. He was like a mad scientist. He had all these tables spread out all over the loft with slides, negatives, prints, and all his equipment and cameras and lenses everywhere. He worked day and night. He always had an assistant or two around, and I never knew where he got the money to pay them. He was as broke as I was.”

In addition to photographing the jam sessions, and despite his shrinking bank account and ballooning drug habits, Smith managed to obtain an array of mobile audio equipment, and with the same fanatical devotion that he gave to his photography, he began to wire the top three floors of the loft with microphones. "One time, we were playing in a session in Dave Young's fifth floor," Bill Crow recalls. "We kept hearing this buzzing noise and didn't know what it was. It sounded like a grinding noise. We finished a tune, and all of a sudden, this puff of sawdust pops up out of the floor, right between Freddy Greenwell's feet. It was Gene Smith drilling holes for his microphones. He had the place wired like a studio.”

Smith's collection of 1740 reel-to-reel four-track stereo tapes from the loft years, organized at his death, filled fourteen cardboard boxes. The tapes that have labels list the names of 129 different musicians. In total, there are more than 300 musicians recorded on his tapes. In addition to the jazz sessions, Smith recorded random loft dialogues, street noise, telephone calls, and a remarkable cornucopia of things off radio and television. He recorded late night Long John Nebel talk shows with callers claiming to have seen UFOs or been abducted by aliens. He recorded John F. Kennedy giving speeches and Walter Cronkite reading Cold War news reports. There are speeches by MLK and roundtable discussions in Civil Rights with MLK, James Baldwin, and Malcolm X. There is the 1960 World Series and the first Cassius Clay-Sonny Liston fight. There is Jason Robards reading Fitzgerald’s “The Crack Up” on the radio and “Waiting for Godot” and “Treasure of Sierra Madre” on TV. There is Shakespeare being performed in Central Park. And there is music, a lot of it: Met Opera performances of Britten’s “Peter Grimes,” von Karajan conducting Verdi’s “Requiem” in Salzburg, and Penderecki’s “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima” taped from WNYC.

But Smith’s main challenge was to record the people in the loft. He once asked a visitor, “Do you mind if I turn on my recorder in case something brilliant happens?” He gained sustenance from the musicians and identified with their need to test themselves in a noncommercial setting. "They were searching for something they can't find in their club dates," he said in a 1965 lecture at the Rochester Institute of Technology. "One night, a saxophonist named Freddy Greenwell came in after midnight on a Sunday night. A drummer named Ronnie Free was there. They started jamming together, and they continued to play until Friday, almost without stopping. Ronnie was a brilliant young drummer, and he drove the session along with tremendous fury and grace. He was working on something, searching for something, and he kept playing until he found it. Many different musicians dropped in throughout that week and played. They'd leave, and Ronnie and Freddy kept right on playing. It was an amazing show of determination. I was inspired by it. I try to put that level of determination in my own work.”

The Smell of Flowers

In his 1969 Aperture monograph, Smith wrote: “The loft I live in, from the inside out. A dirty, begrimed, firetrap sort of place, with space. My pictures from this loft have claimed more film than I have ever given to any project. The reasons: On the outside is Sixth Avenue, the flower district, with my window as a proscenium arch. The street is staged with all the humors of man, and of weather, too.”

Theater obsessed Smith throughout his life. Along with music, he claimed theater as his most important influence, specifically citing the work of O’Neill, Williams, and O’Casey. He said these playwrights helped him “solve problems” in his photography. The visual sequences of literary and staged drama — the build-up of tension and the release — he sought to achieve in his photojournalism. It was a blend of pure documentary work and Smith’s romantic, melancholy, sometimes melodramatic cast of mind. His friend, photographer Robert Frank, remembers him fondly today, “He was an astonishing man, his passion and his belief in whatever he would do. Since then, I haven’t met anyone that comes near that passion and belief in what he does and what it should do, and the effect of his work. He believed it would change the world, and nobody today of the younger people think like that. I haven’t met them.”

After Jimmy Stevenson moved out of the building in 1964, Smith took over all three top floors of the building, except for Hall Overton’s space on half of the fourth floor, and made them the base of his photographic operations. During the opening night of his legendary 642-picture retrospective at the Jewish Museum in 1971, Smith was still frantically making prints and having his assistants carry them from 821 Sixth Avenue to the museum. He lived in the loft until later in 1971, when he was evicted, just as he was setting off for Japan to photograph the mercury-poisoned fishing village of Minamata, a project that would bring him the most acclaim of his career.

Smith and Overton shared a wall in that building for fourteen years, two combat veterans from World War II — two exceptionally creative minds — side by side in a decrepit building in the center of Manhattan. These guys were the opposite of the suburbanites that John Cheever and Richard Yates portrayed in devastating fashion in their fiction of the period. But they weren’t self-conscious rebels or Beatniks, either. They worked too hard, cared too much, were too sincere. They both died too early, of self-destruction.

In letters written in 1978, not long before his death, Smith expressed a wish to put together a book of photographs from his years at 821 Sixth Avenue. But nothing ever happened. He once remarked that legendary producer John Hammond from Columbia Records planned to visit the loft to hear a selection of Smith’s tapes, but there is no indication that Smith tried to do anything commercial with his tapes. The tapes were part of a 22-ton archive that was deposited at the Center for Creative Photography (CCP) at the University of Arizona in 1978. Coming to terms with Smith’s mammoth photographic collection — negatives, contact sheets, and prints from his non-stop life’s work — was a daunting challenge for the photography archivists at CCP by itself. The tapes sat waiting to be preserved and cataloged. Working with the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, we raised and spent more than half a million dollars simply to transfer Smith’s tapes to digital files. By summer of 2008, the transfers were completed. 1,740 reels of tape yielded 5,079 compact discs.

“Hearing these tapes today is like being taken back half a century in an H.G. Wells time machine,” says Free, who is seventy-two years old today and plays drums at a secluded resort in the mountains of Virginia. “I’m able to hear myself playing jam sessions in 1959 or 1960, hanging out with dear friends who are long gone, passed away…Zoot Sims, Hall Overton, Fred Greenwell, Pepper Adams, Sonny Clark, Eddie Costa, Gil Coggins…Gene Smith’s tapes bring these people alive for me. To hear myself playing with them in these sessions, it’s an opportunity I never dreamed I’d have again.”

Bassist Jimmy Stevenson left New York and disappeared into obscurity in the 1970s. It took three years and the serendipitous help of a friend to find Stevenson and his wife making and selling wind chimes on the side of the road in California’s wine country in 2003. “You can’t imagine,” says Stevenson, “somebody calling you up out of the blue and telling you that they’ve got tapes — many, many hours of tapes — of you talking and playing music forty-five years ago. Hearing these tapes is like somebody playing back your memories for you, only these are memories you forgot you had. But these aren’t just memories, this is real!”

Today the smell of flowers after a sweaty night of jamming is still alive in the memories of many of the loft's habitues. "I remember coming out of that loft in the morning and being overwhelmed by the aroma of fresh flowers," Dave Frishberg says. "It was ironic," Steve Swallow says. "Here were the dregs of the 1950s jazz scene, on their way home at dawn, mixing with the flower shop owners who were unloading fresh flowers off of flatbed trucks. Dawn was always the best time to smell those flowers. The streets were quiet. The light and the air seemed new. I loved coming out of that loft and smelling those flowers.”

About the author

Sam Stephenson is a writer from North Carolina, now based in College Station, Texas. He is the author of a biography of Smith, Gene Smith’s Sink, as well as Dream Street: W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Project and The Jazz Loft Project: The Photographs and Tapes of W. Eugene Smith from 821 Sixth Avenue. He is also the ghostwriter of Don't Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You, a memoir by Lucinda Williams.

Sam will speak about Eugene Smith’s photography at the Wisconsin Book Festival in Madison, Wisconsin, on Saturday, October 21, 2023, at 4:30 p.m. Admission is free, and all are welcome. Please, join us!

Love how you’ve migrated to Substack. It’s a fantastic medium for engagement. Look forward to reading this later. Jazz and Photography. Match made in heaven :-)

This is just brilliant...the photos, the essay...

I swear I can hear the music and smell the flowers.