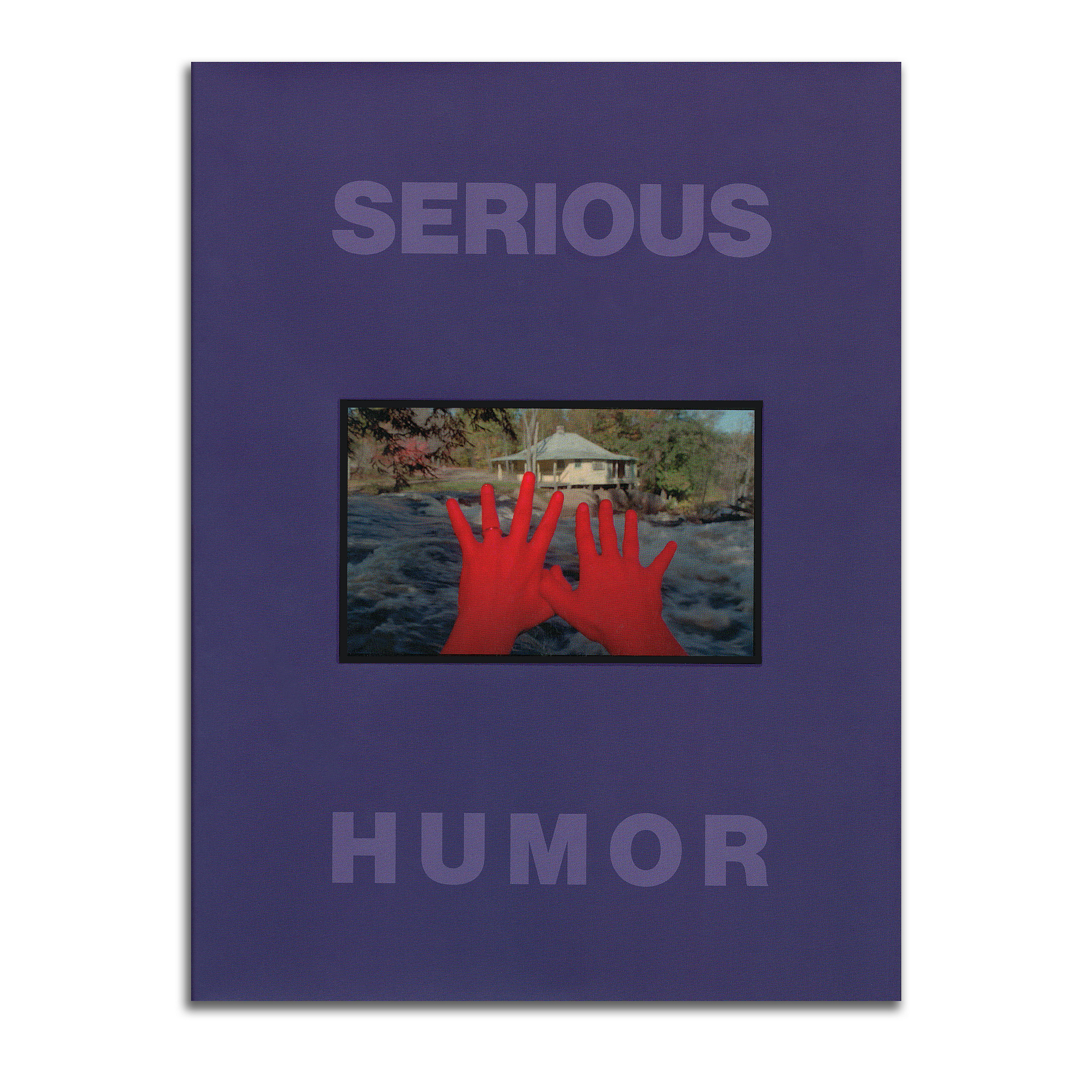

Serious Humor

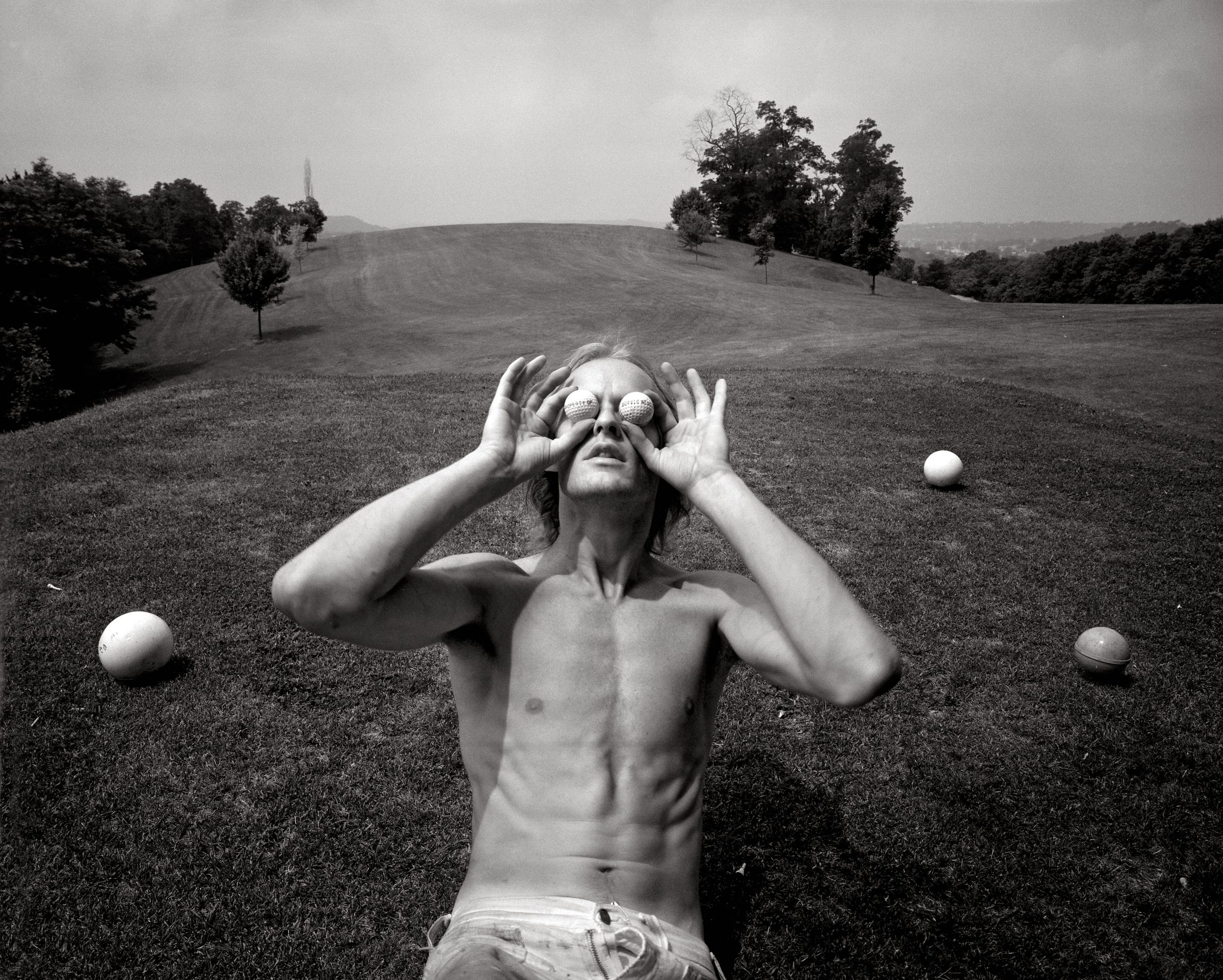

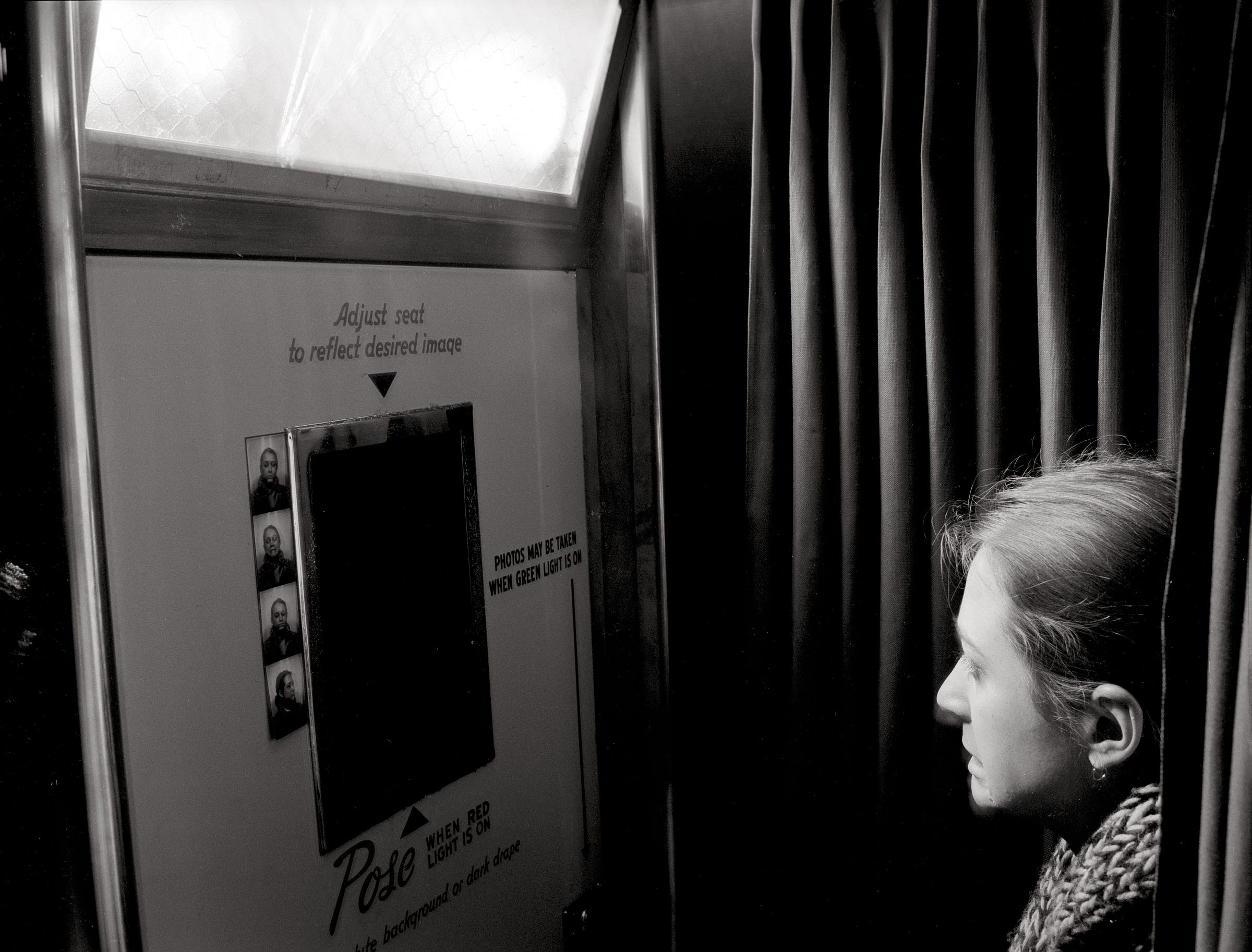

Michael Northrup's spontaneous surreality

Hey, friends — Andy here. This week, something a little different: I’m handing over the reins to two photographers, Pete Voelker and Michael Northrup, to discuss Mike’s new book, Serious Humor (Spotz Studios, 2025). I’ve admired Mike’s photography for years, and I think you’ll agree, it’s out-of-the-box and completely original. I enjoy hearing artists talk about their work, and this is a fun conversation. Since it’s included in the book, today’s interview offers a sneak peek of what you can expect if you pick up a copy for your collection. I’m giving away a signed copy of Serious Humor below; read on to learn more. I’ll let Pete take it from here. Enjoy!

I first met Michael Northrup during my undergraduate years while studying at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). My first photography internship was with him in Baltimore in 2007, and that experience had a major impact on how I understood and approached photography. His work was completely different from what I was learning in my program; more experimental, more playful, and deeply personal.

Beyond technique or aesthetics, Michael gave me some of the best advice I’ve ever received. He encouraged me to move to New York, go out every night, talk about art, talk about work, and immerse myself in the scene. He told me not to shy away from commercial work but to let those opportunities inform me as an artist and professional. That advice has stayed with me, and I’ve been grateful to be able to call on him in the years since I left Baltimore.

This discussion is a reflection of our ongoing conversations about photography, process, and the balance between personal and professional work. I wanted to capture his thoughts in a way that feels as natural and insightful as the conversations we’ve shared over the years. — Pete Voelker

Pete: Let’s start with the basics; what drew you to photography?

Mike: I was a terrible student. After high school, the Vietnam War was raging, and I bounced between schools, eventually landing at Ohio University without a clear direction. I just sort of covered my eyes, dropped my hand on a topic, and it landed on photography.

They had a big photo program; about 300 people in Photo 1, and by senior year, only 15 to 20 were left. I fell in love with it. What really cemented my path was wanting to get out of southeastern Ohio. I wrote to several well-known photographers: Ansel Adams, Brett Weston, Paul Caponigro, Minor White, and Jack Welpott. Most said no, but Jack said, “Come to California.”

He was married to Judy Dater at the time and introduced me to Imogen Cunningham. She had just fired her assistant for leaving the dry press on overnight, so I could have worked for her. I also met Frederick Sommer through Jack; he was brilliant, spoke seven languages, and when I saw him give a talk at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, it was like pure poetry. Spending time with those people made me realize photography was my path.

After that, I got a job in Boston and wrote to Minor White again, telling him about my studies with Jack. He invited me to his home for private study with a small group. I only attended a few sessions; maybe five or six, before returning to Ohio, but that experience was significant. Minor had such a unique way of seeing; his approach was deeply meditative.

That’s an unreal lineup of people to cross paths with early on. Sounds like it wasn’t just about taking photos but about understanding photography on a deeper level.

Exactly. Sommer in particular changed how I thought about photography. When he spoke, he didn’t tell stories; he just thought out loud. He had this poetic, almost surreal way of seeing things. He was also friends with Max Ernst and Yves Tanguy, two major Surrealists. That kind of thinking made me realize photography didn’t have to be just about capturing what was in front of you. Sommer also introduced me to an exercise called ‘skip reading,’ which was something the Surrealists practiced. You take a book, let your eyes randomly scan the text, and read aloud whatever words jump out. He showed me some of his own skip readings, even did them with Shakespeare, pulling fragments into poetic phrases. It changed how I thought about language, structure, and randomness in art.

Shortly after that, in 1972, I met Cherie Heiser. She was the director of Center of the Eye in Aspen, which was one of the most well known photography workshops at the time. She later moved it to Sun Valley, Idaho, and I had the opportunity to teach a full summer of workshops there. A lot of big names passed through that space, and it was another experience that really expanded my perspective on photography and the people involved in it.

What is your connection with SAIC in Chicago?

I went there. I got my MFA.

What year was that?

That would be 1980. Before that though, I went to grad school in San Francisco because I thought after studying with Jack, ‘what could be cooler than going to school in San Francisco?’ So I drove all the way out and I went to Lone Mountain College. The guy that was teaching there was Larry Sultan. Do you know Larry?

Oh, yeah, I mean not personally, but I know his work.

He was teaching there along with another guy named Greg McGregor. When I got out there, I asked my girlfriend at the time; we’d been living together for about a year or two and I thought I could just say, ‘Okay, well, see you in another two years.’ I got out there and I go, ‘What the fuck?’ She flew out. We got married. This was in the fall. By November, I said, ‘This school sucks.’ It was a very weak program. Larry’s just a great guy, but the program itself was not good. I left the school. I spent a year out and then reconnected at SAIC.

Was there somewhere along the line, working with different people and studying in different places, that sparked your interest in strobe work?

It was just as if somebody put a ring in my nose and just started pulling me through it. I look back at my images now, 40, even 50 years later, and they take on different meanings. They evolve, and so do I. When I see them, I sometimes think, ‘What the fuck got me to do this?’ And the truth is, I don’t have one clear answer.

Circling back to Sommer and surrealism, your experimentation with flash and color starts to make a lot of sense to me.

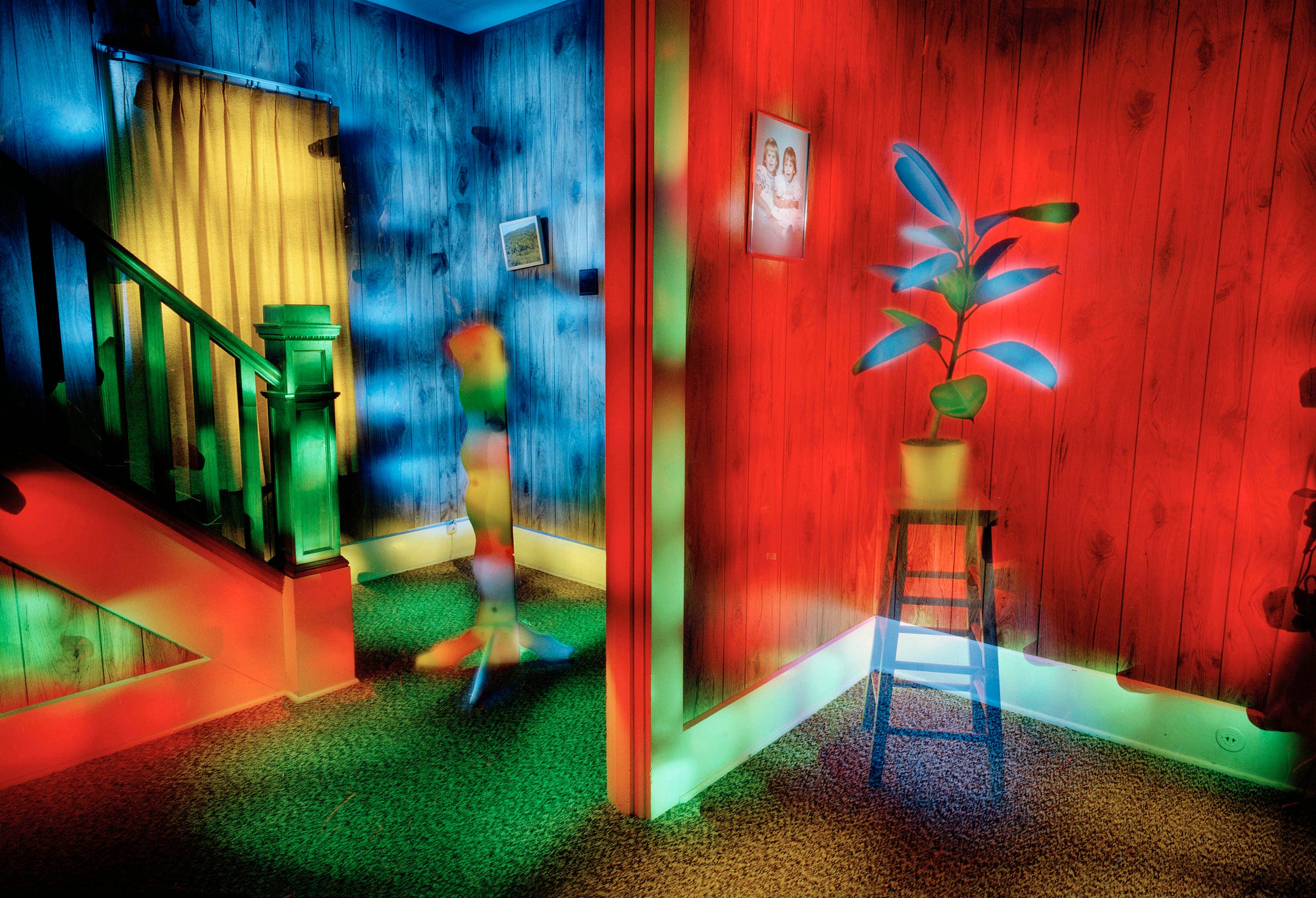

It really started from looking at photographers like Lewis Hine and Weegee. Weegee’s use of flash fascinated me; his photos felt like he knew exactly how the light and shadows would shape the image. Diane Arbus’ Jewish Giant also stuck with me, the way the big, harsh flash created this surreal, exaggerated presence, him towering over his parents in their living room. It wasn’t like those photographers were trying to develop working with the flash, they used the flash because they needed it.

But for me, I fell in love with the light. I was using a 4x5, which was cumbersome and slow. I did a couple photos and I go, OK, now I need a different camera; because I’m going to do this. So then I got a medium format, and it made the whole thing much easier. When I started my flash work, I was shooting black and white, but around 1978, color became more accessible. At first, I didn’t know what to do with it, I was just photographing fire hydrants and yellow curbs, and I was bored shitless. A visiting teacher gave me the best advice: ‘Forget its color. Shoot like it’s black and white.’ That freed me up.

One of the moments that solidified my use of color was a photo I took of a man in Chicago wearing a blue visor. The visor cast this intense blue light on his face while the rest of the image looked normal. Another moment was at a restaurant with my wife; the neon sign in the window bathed her in this neonic red light. That’s when I realized I could use colored gels to shape an image.

That visor photo is in the edit I made for this book; it really pops.

That was a big moment for me. It made me think differently about using color.

I still bounce between black and white and color, I think I like color more but often find myself gravitating back to black and white. But speaking of gels, can you walk me through your light painting technique? I think people see those images and don’t realize how much goes into them.

Yeah, it was a process. I didn’t like the idea of shutting the room off from all light and hurriedly running around strobing. I didn’t want to do it that way. So, I started developing this technique of using a high shutter speed with a normal aperture, with the high shutter speed keeping the daylight at bay. That allowed me to paint with colored light in normal environments. So, I realized I could actually paint light, colored light, in a normal, you know, ambient lit environment. And it just opened up all kinds of doors.

Some of those interiors where it’s just really massive colors everywhere, they took maybe two hours, three hours to do. And every time I would pop a light on a little part of something, I would have to walk all the way back to the camera, cock the shutter, walk back where I left off. I’d still have a latent image in my brain because I’m staring at the flash, so I see the boundaries. It allowed me to go back to the camera, and then get back to the subject, ready to pop the next strobe. And later, to control the boundaries of the light, I built a masking device; a glass panel in front of the camera with a matte board cut into shapes. The panel and the camera were both under a dark cloth. I’d pull one piece of the matte board off, look through the camera at what I’m seeing through that opening, go out there, strobe it while exposing the film, plug it back up, pull the next piece off until I’ve gone around the entire image. All done on one negative. So, if you blow any one strobe, the whole thing’s ruined.

That’s a crazy level of dedication. How were these images received initially?

I’ve been told that some of these images look garish because I’m strobing everywhere I can. And I’ve kind of accepted that. But I just think they’re so fantastic. They’re not to be seen as anything subtle or beautiful. I just look at them as fantastic.

I have one in the edit with the figure, it’s really intense the amount of strobes and the crazy use of color, maybe it’s a mannequin or a cutout on a table. Super successful.

Yep, I know it. When I did that and I printed it, I had one of those wonderful photo experiences where you go ‘damn’ and your heart starts going. And you get excited and you’re looking at it going ‘fuck, man, fuck’. I was teaching at Shepherd College and I took that in and showed the faculty right away. So I knew that I hit something that I really like.

That process seems to be about control and awareness, it’s interesting because there’s so much of what feels like spontaneity in a lot of your photography. Do you feel like there’s a big separation between those types of work?

Yeah, I always felt it. That’s one of the reasons I totally gave it up. I took it to the point where I just couldn’t go any farther with it. And I wasn’t happy with just going, well, this works, so I’m going to do 10 or 100 of these. I don’t like to work that way. To me, every shot is unique, absolutely unique and experiential. So, these things got to be very complicated and very time-consuming. And I was literally running out of ideas.

Eventually, you shifted toward commercial work. Taking these skills with you, was that intentional?

Yeah. I spent the ‘80s showing work in juried exhibitions, but the fine art world moves slowly, it’s so sleepy. In 1990, I started doing commercial work, and it was exciting. My techniques translated well; this was before Photoshop, so designers saw my work as something fresh. Commercial clients responded instantly, whereas galleries took years to plan shows. But eventually, I stepped away from the strobe technique. It became too rigid, and I wanted spontaneity again. I love shooting in the moment. My photos have what I call ‘serious humor’. They look casual, but there’s a strong structure underneath. That contrast is what keeps them interesting.

Serious humor is such a perfect phrase for your work. I think I just changed the title of this book.

I once did a show where the curator asked for a title, and I said, ‘Serious Humor.’ He ran with it. I think it really defines what I do. If I’m being funny, I’m very serious about that. Even though so many of my photos are just pretty much looking like they’re off the cuff. If you really look at them, I’m trying to make sense of the structure, building my composition.

How do you approach editing and sequencing? I know you prefer to let others handle it.

I do. I can only look at one photo at a time. If I sequenced a book, it’d just be my favorite images back to back. Editors find connections I don’t see.

What were some of the challenges you faced when being commissioned for commercial work?

I’ve had clients say, ‘Shoot like you did in the ‘70s,’ but every image I took back then was tied to a specific moment. ‘We want you to shoot like that,’ and I’m going, ‘I don’t know if you understand this. These are all like little poems, you know? I mean, I can try’.

But in the commercial world, you’ve gotta be, you know, you’ve gotta know what’s coming. You can’t just try stuff and see what it looks like. Nobody can afford to do that.

That’s a great way to put it. I’ve been shown mood boards with images of mine that just make me chuckle. Every image is its own moment, and sometimes the art director just wants the image from four in the morning on day three of partying.

Unfortunately they can’t, you know, the people call you to shoot, they can’t go, well, yeah, go have fun.

Would you say your work is more narrative-driven or about feeling and intuition?

I think both apply. I refer to the narrative quality, which I’m not even aware of when I’m shooting. It’s just that when I look at these things, I can see where they were extracted from. And so they had this kind of embedded information. I guess another way to put this is when I was at the Art Institute and we were having a big critique of people’s work. You know, there were about 10 of us, and a couple of the teachers were there making comments. What’s his name? Ken Josephson. I don’t know if you know of him or his work. Ken Josephson was a great photographer. He was probably in his mid-forties by the time I was talking to him. And he was the guy who would hold postcards out in front of the camera and line them up with the landscape.

Anyway, Ken looked at my work, and nobody had said anything like this before. He just looked at it and said, ‘This is autobiographical.’ I had never thought of that, but it’s true — all of my pictures are from arm’s length, from what’s going on in my life at that moment. But I don’t think of my work in that way at all. I think they were right in seeing that. But when I heard that, I went, ‘Huh?’ It never came into my mind. I always saw people in my life, in my images, more as props. They just helped me get to a more universal image that was not really about the person but more about an idea.

Another reason I cut heads off: I wasn’t interested in portraits but more in the ‘figure.’ And when I do a portrait, it’s not so much about who, but more about ‘what.’

That’s a fascinating perspective on how photography reflects personal experience, even if you don’t consciously frame it that way. It’s interesting how much of photography is about intention versus intuition. There was a photographer, when we worked together, when I was coming over and learning from you in Baltimore. You introduced me to him, but I can’t think of his name. He had the photos of deer post-hunt.

Oh, wasn’t that Les Krims? He did the Deerslayers. That’s where I first saw his work. He was using flash and those stormy dark clouds, you could still tell there was daylight, but yet the flash was so harsh, you know, it almost looked like night, but just a weird glow in the sky. That use of flash was definitely formative for me.

You had a personal relationship with him right?

I had, out of all my years of doing commercial work, one time I had to fly somewhere, and it was to Buffalo. And I thought, ‘Fuck, he lives in Buffalo. I’m going to see this guy.’ So, I contacted him, and he came to the airport, and we sat there for an hour talking. And about six years ago, when I was being interviewed about the Dream Away book and answering all these questions, I mentioned that I always wanted my work to be somewhere between Ansel Adams and Les Krims. Then, I get this email from Les, and he goes, ‘Hey, I saw one of your interviews and really love your work.’ You know, he did it — Les was doing a search on his name, which he does periodically. I think most of us do, you know, to see what’s out there about us. And he saw that little interview I had where I mentioned him. We struck up a friendship, and he’s been sending me, fuck, he’s been sending me these prints, 11x14, but they’re signed and editioned. He must have sent me about eight or ten of his images over the last few years.

That’s so cool. I love stories like this. I was in Southern Maryland years back and saw someone draining their deer next to a 7-Eleven, it immediately made me think about Deerslayers and ultimately, you.

I think the best thing an artist can do is to influence, I think, or maybe that’s the greatest thing you could say about an artist, is that they were influential in the medium and Les definitely was.

Let me back up on something, I hate to get techno. I meant to say this when I was talking about the light painting and the mask device. The only thing I want to add to that is, we were talking about the method and how I would have to walk all the way back to the camera, cock the shutter, and then walk back to the object. Later in the 90s, I had a motorized camera system. So I could do it all remotely.

Oh, I didn’t know that.

Well, I’ll go sideways here with you for a second. I had a Bronica ETR and a motor drive, and when I got those, I had no idea that they had a plug in the back of the motor drive, and that would be what would trip the shutter, and then it would have an automatic cocking mechanism. And I had a radio release on my belt, and that would fire the camera. The slave on the camera would fire my flash, and then it would cock the shutter.

That’s awesome. Embracing technology.

It would be like, pop, zip, pop, zip. It would go like that. Instead of pop, walk back to the camera, 10 seconds, 15 seconds, and then pop another.

You know, you really encouraged me to go for it. You also told me not to be scared of or too pretentious to do commercial work, which I think is amazing. In the art school world, everyone turns their nose up at it, definitely in undergrad.

Oh, yeah, of course. It’s funny when you say that because when I taught at Shepherd College, the chairman said, ‘I want you and the graphic design guy, who you’re sort of paired with here in your curriculums — you know, they kind of overlap a little — to go up to the University of Delaware. I heard that the photography department and the commercial, whatever, graphic design department have a good relationship, and I want you guys to go out and see what’s going on.’

So, we go up, and we go into the fine art photo department, and we say, ‘We’re up here because we’re doing some research, and we hear you guys are really working well back and forth with the graphic design.’ And they looked at me and they go, ‘Are you fucking kidding? We don’t do that. Those guys are shit.’ I’m scratching my head, and I realized it wasn’t the fine art department; it was the photographers in this commercial/editorial newspaper curriculum that they had going. Those guys were the ones that were tight. So, the fine art photographers were just sticking their noses up at the idea of collaborating with a commercial person.

Not a single teacher or class was prepping me for commercial work, I had little understanding that artists and photographers did this regularly. I really credit you for allowing me to think differently and not be afraid to approach commercial work.

You know, when I left the Chicago Institute, it was like, ‘Goodbye, go find your audience.’ And that was it. They said it with a smile, you know. The whole time I was there, and everybody — just about everybody — the only thing you could do after that was teach. So, you know, 80% of us were working toward teaching. They didn’t have a single fucking class on how to teach photography effectively to undergraduates, you know, or anything that dealt with teaching. It was just like, ‘Hang out, do your stuff; that’s cool. Oh, we like that one. Okay, bye. Find your audience.’

So what advice would you give to photographers today?

Shoot from your heart. Be true to yourself. Don’t try to be someone else. There were three people in my life I asked, out of the blue, for their best advice: Arnold Gassan, who was head of the photo department at Ohio University in Athens; Jack Welpott, who headed the photo program at San Francisco State College in 1970; and my dad, who was a doctor, a surgeon, and a coroner.

Arnold’s advice was in a story: ‘In the mid-’60s, I went to Aspen during the photo workshop season looking for old buddies. I walked all over town and couldn’t find anyone. So, I went to the town square fountain, sat down for a few minutes, and slowly started to see all my friends.’

Jack’s advice was in Latin: ‘Illegitimi non carborundum’ (Don’t Let the Bastards Get You Down).

And my dad, the doctor, said, ‘Listen to people. They’ll love you for it.’”

About the photographer

Michael Northrup is a widely respected American photographer whose work blends graphic precision with emotional depth. He is best known for his visual wit and his ability to find extraordinary moments in ordinary life. His previous books Beautiful Ecstasy (2003) and Babe (2012), were published by J&L Books and Dream Away (2018) by Stanley Barker. Follow him on Instagram @michaelenorthrup.

Win a copy of Serious Humor

Submission is easy: Tell me why you want this book!

Email me at flakphoto@gmail.com and tell me why you’d like to add Serious Humor to your collection. The best answer wins. Be creative and have fun with this ;)

I’ll draw one winner from the replies on Monday, October 27, 2025.

That’s it! Thanks again for reading, folks, and for supporting my work. I’m looking forward to hearing from you!

These are great! Photography needs more serious humor!!

It was very long read but was interesting. I like the pictures that play with eyes. They work well.