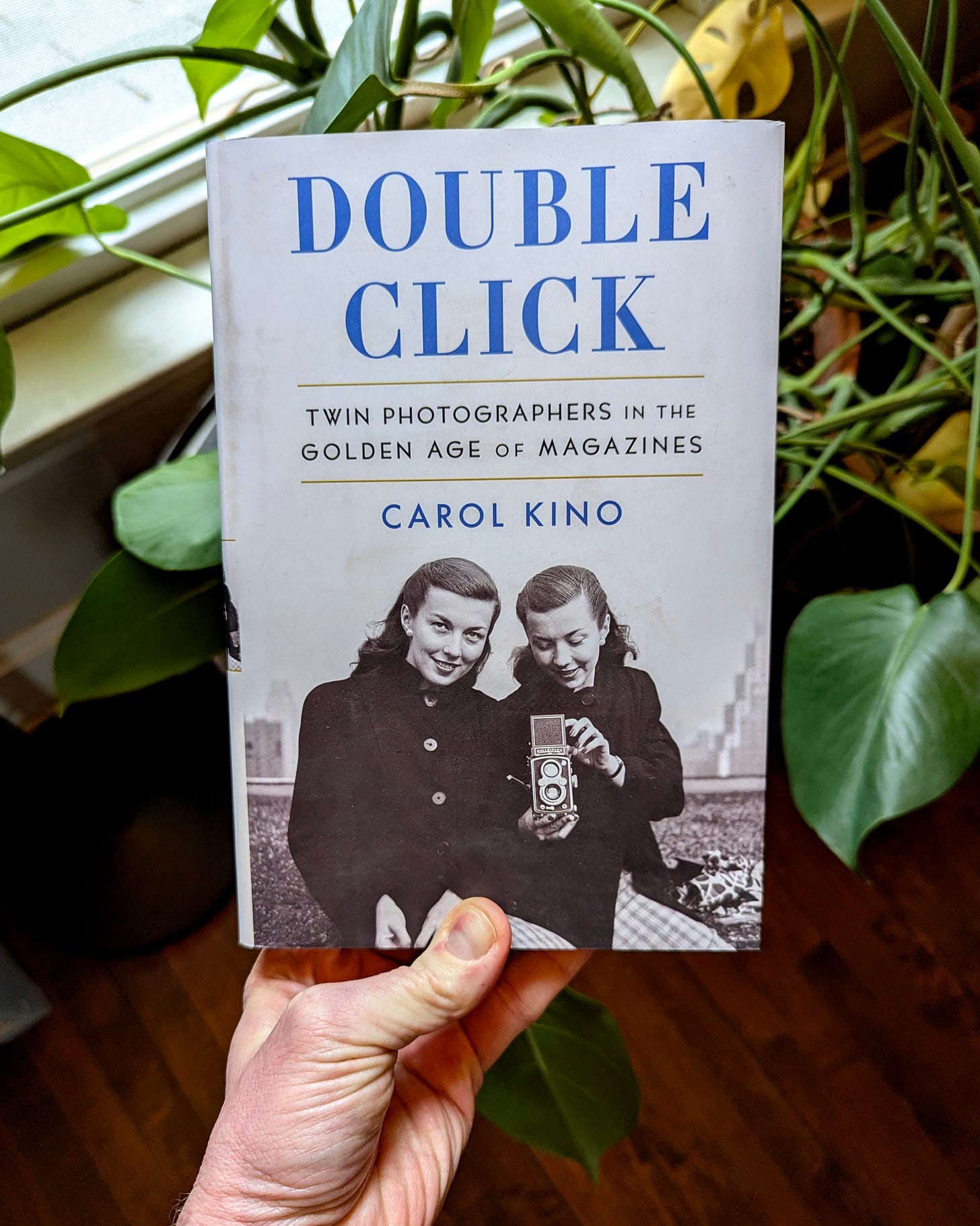

Double Click

Twin photographers in the Golden Age of Magazines

One of the things I love most about social media — in fact, maybe the thing I adore about social media — is how it connects me with creative people. That kind of serendipity still gives me a charge, and despite the drawbacks, social media still delivers meaningful relationships like this in spades.

One such surprise was meeting writer Carol Kino on Bluesky last year. She and I found each other by accident, as you often do on these social networks, and as we got chatting, I learned about a book she published last year. When I saw it was about twin photographers, I was hooked. We started emailing, and I asked Carol how the book came about. She writes:

In 2017, I wrote two stories about a show at Howard Greenberg Gallery that focused on Frances McLaughlin-Gill, the only woman photographer on staff at Condé Nast studio, and her husband, Leslie Gill, an early and important photographer for Harper’s Bazaar. This was accompanied by a show of family photos, many taken by Franny’s twin, Kathryn Abbe, who’d freelanced for the career-girl and youth magazines that flourished during the war, and her husband, James Abbe, Jr., another Bazaar photographer.

Through my research, I was surprised to learn about the numerous women who were active as photographers in mid-century. They pioneered the image of the modern, active woman, yet we barely remember most of them today. Franny, for instance, was Alex Liberman’s second hire, right after Irving Penn, and worked alongside Horst and Blumenfeld. Many of her images are well-known, yet she is not, which seems nuts. I was looking for a book idea. I had written many stories about female artists who had to wait till their 80s to be discovered, but I wondered how someone well-known could disappear so easily.

Fascinating, right? She continues:

My original concept was to write a group biography, but my editor suggested I focus on the twins. That was a great decision, because it let me tell two parallel stories about the liberation women experienced in the 1930s and 1940s, and how everything changed in the 1950s, much like the sea change we’re experiencing today. The twins were also intriguing characters — super-smart, determined, and unusual.

The book has several different strands. It’s a dual biography that covers the twins’ early careers and their studies at Pratt, which established its first photography department just as they began their art school studies in 1937. It also discusses the moment magazine photography really exploded, which coincided with the point magazines became interested in young women and the first career-girl publications were born – all major developments that helped them find careers.

I tried to convey a strong sense of their creative circle and the many other women working in the field at the time. Many of the photographers the twins knew had started as artists, and coming out of the Depression, there was a significant crossover between art and commerce. It was a fascinating time to write about.

I ended up having to conduct a substantial amount of original research, and I spent hours poring over magazines and contact prints to assemble the story. I now have an extensive database of photos by women that I hope might lead to another book. So far, I have not been able to pursue this, but if anyone is interested, let me know!

Scribner released Double Click: Twin Photographers in the Golden Age of Magazines in 2024, and I know many of you will be interested in this book. I asked Carol if we could run an excerpt here on FlakPhoto to give you a taste of her research, and I was delighted when she agreed. Double Click is a tale of a bygone era that sheds new light on our photographic history. Carol’s work will resonate with many of you, so I’ll let her take it from here. Please let us know what you think in the comments.

The McLaughlin twins decided they wanted to be photographers in their second year of art school at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, right after they had talked their way into part-time jobs as assistants in the photo lab. Franny had recognized her destiny as soon as she took her first picture of a Myrtle Avenue el train, thundering over the rusty steel tracks that cast bars of light and shadow onto the storefronts and people below. At that moment, she said, “I knew instantly I was hooked.” Kathryn, known to everyone as Fuffy, felt the thunderbolt the first time they walked into the studio. “Right from the beginning, we somehow sensed that it would be our chosen career,” she recalled later. “It seemed to be the wave of the future.”

It’s hard to know with certainty what it was about photography that grabbed the twins, how they became “enslaved by the djinn in the black box,” as the photographer Lee Miller once put it. People didn’t make a habit of dissecting their emotions in those late-Depression years. But it probably had something to do with the puzzle-like challenge of figuring out how to compose a shot with the twin-lens reflex camera they had received as a high school graduation present and traded back and forth: when they peered down into the viewfinder, the camera returned a mirror image of the scene they were aiming at; there was no way for them to see what they’d captured the right way around until they developed the negatives. Then came the empowering transformation that they could bring about as they printed the pictures in the darkroom — the “magic of light and lens,” as Fuffy once described it — where a skillful deployment of chemistry, temperature, time, and light could change the way the final image came out.

Photography was a magic carpet, out of the Depression and into the future.

There was also the sheer excitement of experiencing the luck involved in capturing the “decisive moment,” the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson later called it — being in the right place at the right time, as a group of teenagers walking in a park wheeled around to face the camera, or a mother and child stepped off a sidewalk onto a broad expanse of paving stones, or the instant the sun raked light across the brick walls of a factory at twilight as women poured out of its doors.

For the twins, who had already spent their teenage years making paintings, it must have been electrifying to suddenly be able to fix reality on the page in a more immediate way than by daubing oils on canvas. Among the American avant-garde of the time, the all-important task was to define an art that was their own and distinct from that of Europe, and some photographers felt they were working in the perfect medium to depict a country that was brash and new. In 1935, Dr. M. F. Agha, the longtime art director of Vogue, who had helped push photography onto the pages of that magazine, described photography as the quintessential American art form — “a Real American Native Art,” he called it — in the introduction to the first edition of U.S. Camera, an annual that compiled two hundred of the year’s best pictures.

“Romanticism in art is dead,” he wrote. “The skyscraper is the thing to admire.… The poster is better than the fresco; the saxophone is to be preferred to the hautbois; the movies to the theatre; the tap dancing to the ballet, and the photography to the painting.”

Sure, Agha was being somewhat arch and ironic — but he also meant it. Even then, in one of the worst years of the Great Depression, Americans were such passionate camera and photo buffs that the annual, filled with more than two hundred photos of every variety — nudes, tarantella dancers, stargazing couples, sailboats, carefully composed still lifes, landscapes, family scenes, fashion shots, in color as well as black and white — sold out its fifteen thousand copies, at $2.75 each (more than $60 today), in only a month. Its publication was followed by a U.S. Camera exhibition of seven hundred pictures that opened at Rockefeller Center, a glamorous new office complex of limestone towers that was rising in midtown Manhattan. The show attracted huge crowds and continued to draw hundreds of thousands more viewers as it toured, going on view in department stores and exhibition halls in seventy-five cities around the country. The display and its tour became an annual event.

More photography shows, annuals, and magazines followed. In 1937, the eight-year-old Museum of Modern Art opened a huge survey that put the medium of photography in historical perspective; it toured the country for two years. An even larger show, the International Photographic Exposition, arrived in 1938, across town at the Grand Central Palace near Grand Central Station, where during a single week over a hundred and ten thousand people came to see about three thousand pictures, ranging from Mathew Brady’s Civil War daguerreotypes to pictures of starving migrants by Dorothea Lange, who had been commissioned by the federal government to chronicle the ravages of the Depression.

Photography was also infiltrating American magazines, replacing etchings, watercolors, and woodcuts as the snappiest and most up-to-date way to illustrate anything, whether it was a newspaper story, a work of fiction, or a fashion spread. Soon, a new sort of magazine that told stories in pictures instead of words became the rage. The first of these, Life — styled in its offering prospectus as “THE SHOW-BOOK OF THE WORLD” — was launched in 1936 by Henry Luce, the publisher and editor in chief of Time magazine, the year before the McLaughlin twins entered art school. Its opening cover pictorial focused on the gritty Wild West frontier towns that had sprung up in Montana around Fort Peck Dam, one of the great Depression-era work-relief projects on the Missouri River. It had been shot by an intrepid woman photojournalist, Margaret Bourke-White, who brought the hamlets’ sheriffs, mechanics, barkeeps, hash slingers, laundresses, and ladies of the night straight onto city newsstands and into American homes.

Life was followed by the pocket-size Coronet, which boasted thick portfolios of great historical artworks in color, brand-new black-and-white photographs, and thumbnail biographies of contemporary photographers and sold out its first quarter-million run in two days. In contrast to Life, which typically published all-American pictures, Coronet often featured works by Europeans, such as Cartier-Bresson, André Kertész, and Erwin Blumenfeld, who used experimental developmental processes to create exhilaratingly arty shots of nude women, their bodies floating alluringly in water or veiled in clouds of tulle.

By 1938, the year the twins decided on their profession, the leading women’s magazines had also begun to feature photos of women, in color, on their covers — magazines such as Vogue, Mademoiselle, and Ladies’ Home Journal — so while walking past a newsstand, instead of seeing a watercolor of a lady lying on a chaise or peeking out from behind a bouquet, one saw a row of real faces looking back.

But perhaps the moment that most dramatically demonstrated photography’s importance, at least in New York City, was the opening of the 1939 World’s Fair in Queens, an exposition designed to lift America out of the Depression and bring nations together under the theme “Building the World of Tomorrow,” even as war raged overseas. There, amid displays of futuristic new products such as plastics, air-conditioning, and television, pavilions that advertised the art and culture of different lands, and a diorama called the Democracity — a model of the town of the future that showed the astonishing ways in which Americans would one day live, travel, and work when the world had moved beyond hunger and war — the Eastman Kodak Company celebrated the hundredth anniversary of the medium’s invention with the “Cavalcade of Color,” a twelve-minute long show of Kodachrome slides projected onto a towering curved screen wider than a football field. As brilliantly colored pictures — of people, families, brides, fields, mountaintops, animals, flowers — circulated and dissolved into one another, music played, and a man’s voice spoke of the wonders of American life and Kodak technology:

Our camera fan, like a Rembrandt, sees beauty everywhere and helps us to see it, too.… Photography brings to us the beauty and majesty of this great country of ours. This great country, where centuries ago men began to build with a spirit, with a tolerant reverence, which is a part of our national life today.

Photography also permeated many other aspects of the fair. There were picture exhibitions throughout, and booths where visitors could watch photos being developed and printed. Every one of the fair’s seventy-five thousand workers carried an identification card emblazoned with a snapshot of his or her face, and anyone buying a multiple-entry ticket likewise got his or her photo on a pass — one that was shot, developed, printed, and sealed to the card on-site, before crowds of eager onlookers.

U.S. Camera, in addition to its annual, had also launched a monthly magazine that year, one of several new photography publications. It dedicated its entire fifth issue to the fair, pointing out which displays were most photogenic, and which lenses and film would work best for which photo ops. Cameras had sold well throughout the Depression — a small camera store specializing in minicameras and their accessories could be as profitable as a car dealership — and the New York Times described comical scenes of greenhorn lensmen stumbling into one another as they rushed to pose shots, and then running to the many camera shops at the fairgrounds for help when their equipment didn’t behave as expected. “Amateurs Swarm over Grounds… but Expert Click Is Rare,” the story proclaimed. “The prevalence of cameras at the Fair has become something of a major phenomenon, almost as impressive in quantity as the number of hot dogs eaten daily and the number of girl shows on the midway.”

The McLaughlin twins were entranced by the fair, visiting it many times, each trip costing them a nickel for the subway ride out to Queens, seventy-five cents for admission, and a quarter to enter each booth. One of their friends, another art student, was working as a mermaid at a booth in the Amusement Zone, in a fun house created by the surrealist artist Salvador Dalí called “Dalí’s Dream of Venus,” which was part artwork, part girlie show. Behind a pale pink plaster facade, beyond a doorway flanked by a pair of monumental female legs, bare-breasted girls in lace-up corselets, fishnet stockings, fish tails, and other mermaid-like attire splashed through water tanks around a nude actress who lay sleeping in a bed, covered to the waist by a red silk sheet, playing Venus. The twins’ visits to see their friend were endlessly thrilling. “You can imagine that we felt truly a part of the art scene when we went to the Fair and watched her,” Fuffy recalled.

So when they returned to the basement of Pratt’s Home Economics building, down into the school’s newly completed photography studio — one of the few places in an American school where students could learn to click expertly — the twins leapt at the rare chance to participate. Henry Luce, the powerhouse editor of Life, had written in the magazine’s original business plan that he viewed photography as a way for ordinary people “to see the world; to eyewitness great events; to watch the faces of the poor and the gestures of the proud; to see strange things — machines, armies, multitudes, shadows in the jungle and on the moon.” Photography was a magic carpet, out of the Depression and into the future.

And for girls with larger ambitions than getting married — or working as secretaries, or teaching children, or swimming topless in a fish tank wearing lingerie — mastering the art of professional photography must have seemed like a pretty good way to make a living. As Fuffy told Dick Cavett on television nearly forty-three years later, while her twin, Franny, looked on, “We just liked it. We didn’t even discuss it. That’s what we were going to do.”

Excerpted from Double Click: Twin Photographers in the Golden Age of Magazines by Carol Kino. Copyright © 2024 by Carol Kino. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Carol Kino’s writing about art, artists, the art world, and contemporary culture has appeared in publications such as The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Atlantic, Slate, Town & Country, and almost every major art magazine. She was formerly a fellow at the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center at the New York Public Library and the USC Annenberg/Getty Arts Journalism Program. She grew up on the Stanford campus in Northern California and lives in Manhattan. Double Click is her first book. Follow her on Instagram, Substack, and Bluesky.

That first color portrait is so contemporary looking. I assumed it was some sort of modern tribute until I read the caption. Bravo.

wow this is great thanks for sharing this! I love how writers like Carol are working to correct the history of this medium we love so much!