Coney Island, 1971

Benjamin Swett's photographic memories

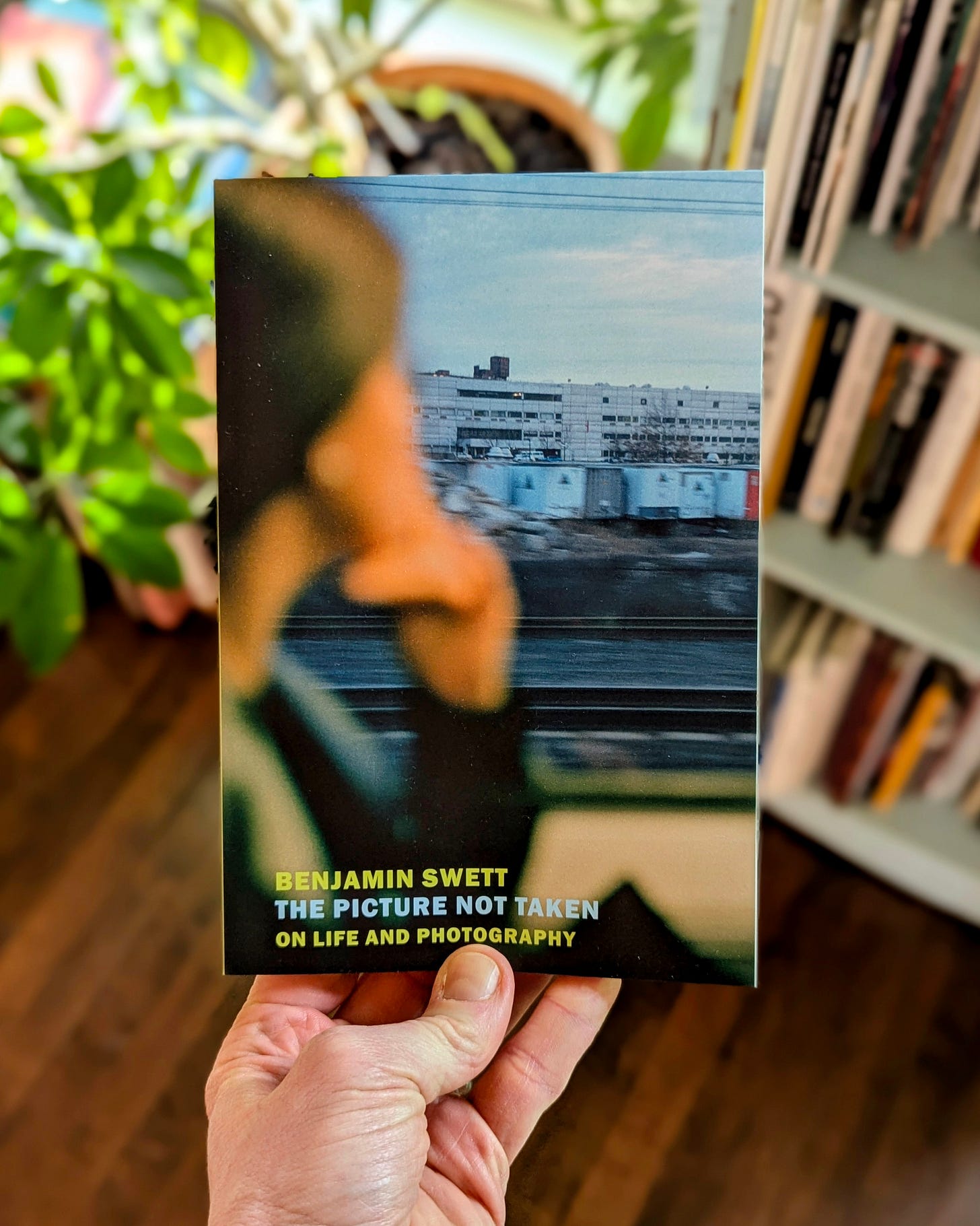

This week, a guest essay by photographer Benjamin Swett from his new book, The Picture Not Taken: On Life and Photography. Benjamin writes about growing up with a father who carried a camera, and I can’t help but feel a kinship with his experience.

Photography can be an art form, but for many, it’s a habit and maybe even a way of life. I’m pretty sure my love for photography was inspired by my mother, who documented our childhood constantly. Clearly, Benjamin’s father influenced him.

This week’s post is a long read, so make time to slow down and appreciate the writing. If you like this piece, consider buying Benjamin’s book. I’m enjoying it, and you might too. Thanks again for sharing your essay with us, Benjamin!

One January day in 1971, my father drove my sisters and me to Coney Island. We bundled up in our winter coats and brought the puppy along. For some reason we did not think it safe, as we marched along the edge of the water, to take the puppy off the leash. Or maybe this simply did not occur to us. There was something ceremonial about that march—how dressed up my sisters were; how close we stood to each other; the fact that we were at Coney Island in winter; the fact that, as I see on closer inspection, we each clutched a camera. Our father, I realize, must have set it up, corralling us together as he backed away from us along the sand, his camera to his eye. On the contact sheet the photo is severely cropped, with instructions to the lab technicians, in red china marker, to “hold crop at feet.” That crop, though, would have cut out all of the shadows—including the shadow of the dog. Why did my father like to crop his photos so much? Why am I always so reluctant to crop? And where was our mother?

Our father was always taking pictures of us, but sometimes he turned his camera on other things. That day at Coney Island it was the flocks of sea-birds flashing above us in the sun. Coney Island is so much like that, the screeches of gulls constantly piercing the crashes of waves and the whine of the wind off the sand. When I think of going to that place, as I so often did as a child, I think of those gulls in particular interrupting the more regular sounds with their fierce cries, which could be like horses whinnying. My father wasn’t fast enough on the focus on this one, and the birds, zooming around on their own courses, came out as hazy ideas rather than fast facts.

My father did not print this picture, as he did not print several on the contact sheet, but to me it is as interesting as the one that precedes it, reminding me not only of the hazy background “aura” of Coney Island with its packs of birds circling in the wind, its smells of sauerkraut and hot dogs from the vendors along the Boardwalk, the potato chip bags and stray pages of newspapers that blow across the wrack, the grayish color of the sand, the sand dollars, lost barrettes, dolls, shells, toy shovels, dead seagulls, dried jellyfish all mixed up in seaweed: but of my father and the complexity of his experience, which I understand better now but could not have seen then; how he, too, noticed things out of the corner of his eye, thought ahead and behind and around the moment, and was always plotting, watching.

That visit to Coney Island happened to coincide with the weekly convocation of the Polar Bear Club. This is perhaps the only thing I actually remember from that day more than 50 years ago: those men and women with their ample bosoms and shaggy chests who one by one, with their hands on their hips, waded into the waves, lowered themselves onto their backs, and burst up laughing in a halo of spray across the sun. I remember my pleasure and amazement watching these—what seemed to me—old men and women frolicking in the water on that frigid day. I imagined that one day I too might join them, and how free I would be and how brave I would be as a member of the Polar Bear Club.

In an old album, I recently found the Instamatic picture that one of my sisters took (square-format, color, faded to aquamarine) of the same man my father had photographed that day. He epitomized the pride and courage I felt looming around me in the world at that time, and which I hoped to acquire. In fact, I have never been brave about swimming in cold water. It is only to save face that I occasionally force myself to dive into icy streams. My wife is much better with extremes of temperature than I am.

According to its web site, the Coney Island Polar Bear Club was founded in 1903 and is the oldest winter bathing club in the United States. Meetings take place every Sunday, November-April, at 1 PM. Membership, the web site says, is currently closed.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes describes how a person being photographed becomes four people at once: “the one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, the one the photographer thinks I am, and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art.” As children, my sisters and I contended with this quadrupling of consciousness whenever we spent time with our father. Even if he did not have a camera in his hand we knew (because he said so) that we were his favorite subjects. I imagine him that day, squaring his fingers around his eye to frame us; to show us, for some reason (as if we cared) that how we sat at that moment, eating hotdogs in a patch of sun outside Nathan’s, would make a good photo. “It is no doubt metaphorically,” Barthes writes, “that I derive my existence from the photographer.” But in our case it was not metaphorical at all; he was our father.

I kind of admired him for it.

Coney Island’s famous wooden roller coaster, the Cyclone, built in 1926, was closed that day in 1971. Snow drifted up the boarded-up arcades of Luna Park as we posed, shivering probably, for another picture. Our father was always posing us like that, to stand casually together and appear as if we were spontaneously ogling something off-camera. Even the dog seemed to know the game.

Unbeknownst to my sisters and me, we were to leave Brooklyn later that year and move to Northern Westchester—part of the vast herd of whites leaving the city in those days for the suburbs. As I look at these pictures, I can’t help but think that my father really was taking them for a ceremonial reason, to commemorate some of the places we had all been together as a family that we were leaving behind. Looking back on that time, I remember how excited I was when I eventually did learn that we were to move and how it never occurred to me, as we prepared to exit Brooklyn and then did so, that I might miss my old friends, my old life, the old places where I had spent so much time. I just walked into my new life and closed the door behind me.

A few days ago, when I asked my father about these pictures, he remembered nothing about them. He said he did not think they had had anything to do with our leaving Brooklyn later that year.

The camera sees more than the photographer. What my father had in mind when he photographed my sisters and me lined up at the top of the grandstand overlooking the Dolphin Show at the New York Aquarium may not have been much more than what he himself later said was on his mind that day: “my amazement at being a husband and father” and “I wanted to capture the setting.” Posing us in front of various Brooklyn backdrops must have felt, in a way, like accomplishing both of those goals at once. But here the setting gave way to the people, and the people—their eyes on the Dolphin show—gave themselves up to the camera, independent of any ideas the photographer might have had in mind.

So: my sister Sarah in her white cotton gloves and rabbit fur hat, in button-down wool coat with fancy embroidery on the collar. Is that a gold pin—shaped like an elephant—on her breast? And my sister Lyn in her not-very-warm-looking ski parka with the wool-lined hood and a broken lift ticket dangling from the zipper. My two sisters expressing in almost perfect juxtaposition the two major forces in our family: the genteel and the sporty. Lyn a girl who was already skiing at the age of five. And Sarah a girl who had been dressed, that day, almost entirely by our proper grandmother in Baltimore. We were people who skied; we were people who wore white gloves and rabbit fur hats; we were people who carried cameras. As for me, in my corduroy jacket with the Norwegian sweater sticking out of the sleeve, all I can think when I look at the picture is how much fancier the camera that I am holding is than are the ones held by my sisters. And: where was my dog? Judging by Sarah’s outfit it was probably a Sunday and we had probably driven to Coney Island with our father after church.

When I ask my father where our mother might have been he does not remember. Was she “busy correcting papers; was she not well; perhaps she wanted a day to herself ?” The idea of our mother wanting a day to herself was not something that would have occurred to me at eleven.

My father took several pictures of the dolphin show, but what interests me most, now, is the apartment buildings filling the background. Standing out sharply, warmly in the winter sun angling in from two directions—from the sky and reflected off the ocean—those buildings appear clean and hopeful; and in the nearly shadowless light that seems to glow on them I can hear the gulls screaming over the boardwalk behind our backs and the splash of the dolphins as they slip, strangely grinning, back into the frigid water of their pool.

In fact those buildings, Brightwater Towers—with their own swimming pool, laundry, garage, central air conditioning, and 734 apartments—had been completed just seven years before, in 1964, after a decades-long rezoning effort by the then-parks commissioner, Robert Moses. When I first came to Coney Island and visited the aquarium as a small boy those buildings would still have been under construction. The aquarium itself, built in 1957, was also part of this push—dating back to Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia—to transform Coney Island from what Moses called a “honky-tonk catch-penny waterfront” into a family-friendly destination. The original New York Aquarium, opened in 1896 at Castle Clinton in Battery Park, at the southern tip of Manhattan, had closed in 1941, also, apparently, at the instigation of Moses, who wanted the land for construction of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. None of this did I know in 1971, yet I could feel all around me, when I looked up from my life and listened to the jackhammers and pile-drivers, that major changes were taking place. I can’t speak for my sisters, but to me the most compelling exhibit at the aquarium, when I went there as a child, was the small, murky tank, just past the killer whale tank, of the Electric Eel. I don’t remember exactly how it worked, but I think you pushed a button, though perhaps it was just a matter of waiting, and a crackling sound would come out of some speakers, or maybe a light would come on, triggered by the dark, snakelike fish writhing all by itself in the greenish gloom behind the glass.

From Coney Island we drove on the Belt Parkway around to Cadman Plaza under the Brooklyn Bridge. Now I see just how much snow had fallen the night before. It seems our father had decided to stop here on our way home so we could all photograph this greatest symbol of everything we had known up until now—and so he could photograph us. He was fascinated by the Brooklyn Bridge and used to tell us, as we drove across it, or even when we saw it in the distance, stories of its designer, John Roebling, and how his foot had gotten crushed by a ferry and he had died before the bridge could be built and his wife and son and daughter-in-law had taken over the work; and of the wooden caissons that were sunk on either side of the East River to support the towers; and of the pressurized air that was pumped into the caissons to prevent the workers from getting the bends; and how some did anyway; and how those gigantic caissons where those men had worked digging out the muck at the bottom of the river had later, when sunk to their proper depth, been filled with concrete. Perhaps because he had grown up in Baltimore, our father was endlessly fascinated by Brooklyn and by the fact that we lived there, and he talked about it the way somebody might a favorite sports team. My sisters and I, who had always lived there (as far as we could remember) took it for granted, and even now it is not the bridge that I notice when I look at the picture but Lyn sticking her tongue out at our father; the seagull flapping through over the river; the garbage truck idling in the turnaround; my bell-bottoms, of which I was quite proud; and the corner of our old gray Ford Falcon, rusted, beat up, site of all our boredom and excitement on trips—soon to be replaced, when we moved to the suburbs, by the fake-wood-trim Plymouth Volare station wagon that would transport me, eventually, away from my family to boarding school and college.

Sarah stepped back into the slush to get a better angle on the bridge. In the picture she took that day, which I have seen, the bridge tower appears massive, like a stone castle above a snowy plain. Even then Cadman Plaza was a turnaround for buses. The one behind Sarah, #25, going to Alabama Avenue, still runs on virtually the same route along Fulton street as it did then. Brooklyn was full of signs and links to places we had never been. (We would not have known, for example, that the area around Alabama Avenue, known as East New York or New Lots, was then in the midst of an infamous racialist blockbusting scheme.) My father took two pictures of Sarah photographing the bridge, this horizontal one with the sun star and a second, vertical one, without the bus, without the flare from the sun, showing the entrance ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge and the top of the Eagle Warehouse building in the background. It was the more traditional, well-framed shot. But I prefer this one for how small Sarah looks against the bus and for the carriage house building and part of the Texaco sign caught in the upper-right-hand corner. That is the Brooklyn I knew. Our parents are hard to pin down about why they left Brooklyn and moved to the suburbs later that year. In truth, like many changes people make in life, this one may have happened for reasons outside the individuals’ willful control. One party wants to make a change and the other party wants to please the first. Financial considerations loom large. There is fear, boredom, restlessness, inattention. My sisters and I think that the move was the wrong one for our father but the right one for our mother. Neither of them could have seen this in advance, however—and who knows what the alternative might have been. We move through life like a submarine without radar, sticking up a periscope to try to see ahead, unaware of the torpedoes coming in from the side.

Of all the pictures on the roll of film my father shot that January Sunday in 1971, the one that gets to me most is the last—a throwaway shot, for my father, never cropped, never printed, never looked at again.

After he took the ceremonial photo of his children on the south side of the bridge (and he was anything if not economical in his use of film: he took just that one exposure) and after he gave Sarah a chance to step back and take her pictures in front of the bus, we walked or drove (probably drove) around to the north side of the bridge where my father, perhaps leaving us in the car but more likely coaxing us and the dog with him across the snow, positioned himself in front of an abandoned warehouse to take a last picture, before the roll ended, of a much longer stretch of the Brooklyn Bridge with the Manhattan skyline in the background.

And here it is that I find myself quietly, respectfully lifting the camera from my father's hands. Now it is me standing there on that abandoned stretch of shoreline on that frigid afternoon in 1971. Smells of the sea, of salt and hemp and fish, whip in on the wind; the steel beams of dockhouses tilt into brine; gigantic cleats rust in the granite sides of wharves; the black pilings and twisted metal gates of abandoned ferry slips stick up at forlorn angles. Standing there in the snow and weeds, engrossed in the rank smells off the water, which are the smells of ‘old New York,’ of my own beginnings in the city and the longer ones of my family; seeing the sun on the harbor and imagining the “numberless masts of ships” Walt Whitman described and the “thick-stemm’d pipes of steamboats”; thinking of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island and the impossibly high curve of the recently-built Verrazzano Bridge; and remembering “the heights of Brooklyn to the south and east”: consumed by these evocations of past and present converging on this rank and weedy spot, I take no notice notice, as I bring the camera to my eye, of the new building rising across the river, the massive structure, soon to be two, that I will one day watch fall.

About the author

Benjamin Swett is a writer and photographer whose books include the essay collection The Picture Not Taken: On Life and Photography and the photo-text narratives Route 22 and New York City of Trees, winner of the New York City Book Award for Photography.

Swett’s recent essays have appeared in Agni, Arnoldia, Salmagundi, Orion, Prism International, and Fiction magazines. He teaches writing at City College in Manhattan and is senior photographer for the Notion Archaeological Project in Turkey. He was named the 2024 Larry Lederman Photography Fellow at the New York Botanical Garden. His photographs are in private, corporate, and public collections, including the Museum of the City of New York.

On Instagram, he is @benjaminswettnyc, and on Bluesky, @benjaminswett.bsky.social.

One more thing…

You'll enjoy his book if you liked Benjamin’s Coney Island essay. You can read more about The Picture Not Taken and get a copy for your library from New York Review Books. I would love to hear your thoughts on the essay, and Benjamin would, too. Let us know what you think in the comments. Thank you for reading!

Fantastic and moving essay from a wonderful photographer and writer. So pleased you’ve brought this work to your audience.

Beautiful essay that frames :) a particular time and place with such detail and care. I come from a family of people with cameras in hands and very much relate. The fact that all three children are carrying cameras is a story in itself!