To photograph is to learn how to die

Tim Carpenter on a philosophy of art (and death)

How’s everybody doing out there?

The lazy summertime vibes are in full effect here in Madison. I’ve been AWOL lately, and I suspect most of you haven’t missed me since you’re doing the same thing in your world. Good for you! That’s the way it should be. I told you before that I wanted to open FlakPhoto Digest up to other photography voices, and I’ve been lining up some guest writers I’m excited to share with you soon. Please drop me a line if you’d like to contribute; I’m open to ideas. This week, I’m trying something new — publishing a book excerpt from one of my favorite imagemakers, Tim Carpenter.

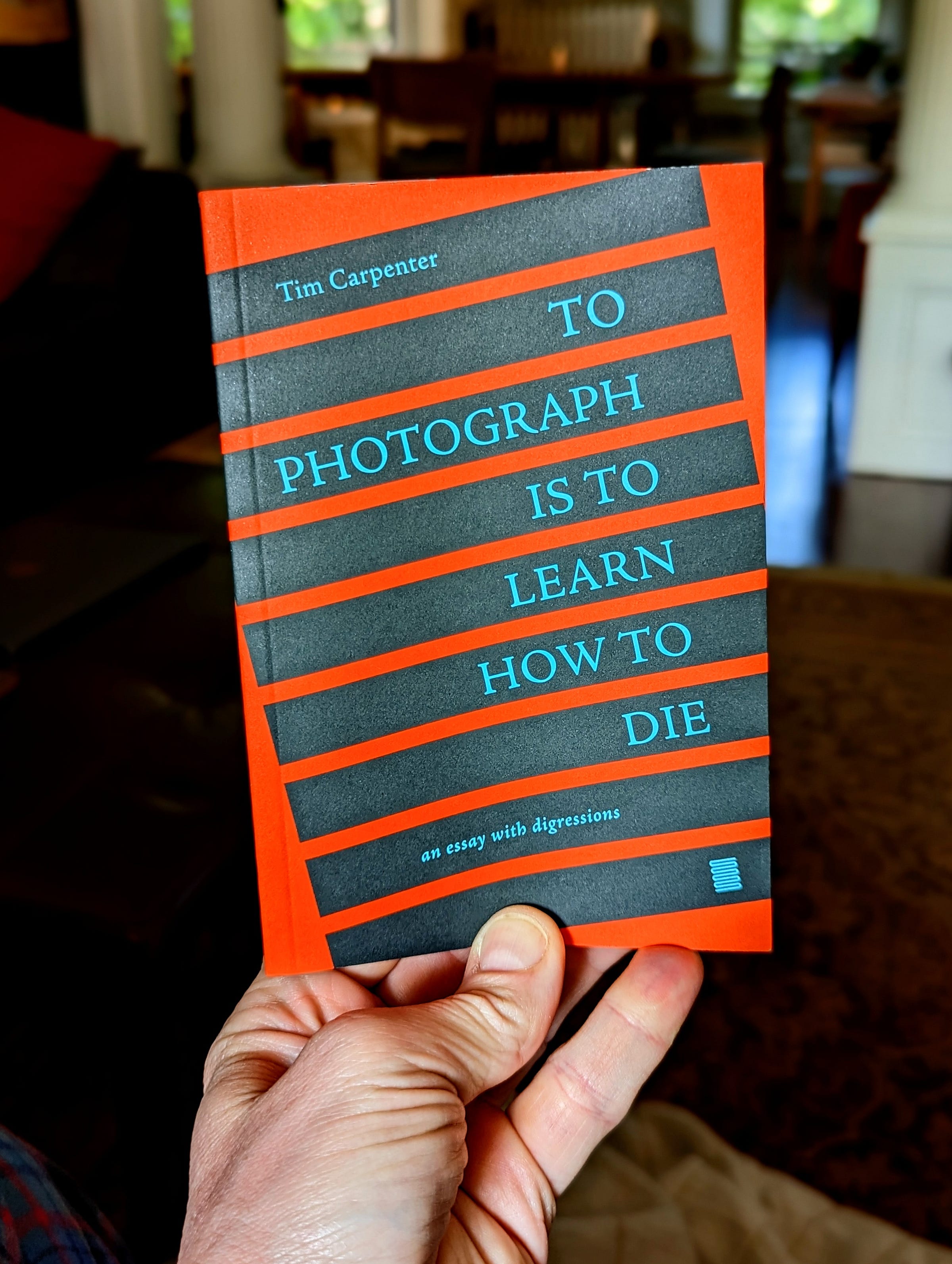

Tim’s latest book, To Photograph is to Learn How to Die: An Essay with Digressions, is so popular it has gone into three printings and is about to go into a fourth. I was happy to hear that and not surprised since I’ve seen people rave about it on social media. But I hadn’t read it yet, so I added it to my summer booklist.

Tim’s a Midwesterner like me. He hails from Illinois and splits his time between there and New York City. Tim’s pictures remind me of the places where I grew up. They’re quiet and meditative. I think you’ll like them. Tim is a sensitive soul, and I loved his book Local objects because it reminded me of the many rural American landscape views I treasure. I asked Tim if we could share some of his new writing here in the Digest so that some of you could get a taste of what he’s been up to lately. Since he’s been giving book talks, I suggested he could set the stage with a brief introduction. He graciously obliged and sent a short recording.

Intriguing, right?

This kind of philosophizing is right up my alley, and I know many of you will appreciate it. I hope you enjoy reading Tim’s preamble, which opens the book.

By the way, I’m giving away a copy of Tim’s book at the bottom of this post — Read on to learn how you can toss your hat into the ring for a chance to win it.

Okay, Tim, take it away…

You are here, and later on you will no longer be here, and you know it. What is not corresponds in your mind to what is. This is because the power over you of what is produces the power in you of what is not; and the latter power changes into a feeling of impotence upon contact with what is. So we revolt against facts; we cannot admit a fact like death. Our hopes, our grudges, all this is a direct, instantaneous product of the conflict between what is and what is not.

— Paul Valéry

I am writing in the early 2020s. The thoughts of many people are properly engaged with the historical and the topical — with politics and ideologies and the like. With events. My head is there, too, but the constant pressure of the external in these years has, perhaps unsurprisingly, also led me more fully into the equally stormy internal. “It is a violence from within that protects us from a violence without,” Wallace Stevens wrote. The human imagination has “something to do with our self-preservation” and “helps us to live our lives.”

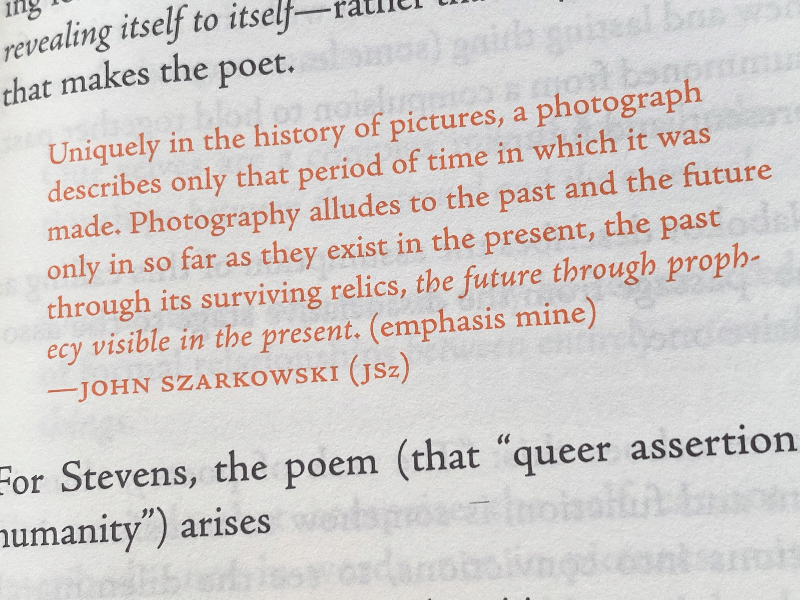

Preserving the self has meant, in my case, making photographs (lots of them) in a conscious attempt to reconcile the conflict between what is and what is not. This vocation has shown me that such reconciliations — to the extent they are even achievable — could never have just happened in my head. What I seem to require instead is the friction of the materially circumscribed activity of photography: an activity that uniquely entangles the actual and the imaginary, and which results in a beguilingly inscrutable product: a new thing in the world that is itself a conditional accord between what is given in the real and what is possible in the mind.

“How shall we learn what it is our hearts believe in?” Archibald MacLeish once asked. For me, the answer is working with and through the camera — a peculiar machine that is the most plainly useful thing I will ever encounter. Which makes me curious about the nature of the desire to make things in this way.

As a foundation, I have to believe that all people know the ache of the conundrum described by Valéry. Yet obviously, only some of us — a small handful, really — are compelled to make something of it: an aesthetic object in which a specific instance of felt life is evoked by the distillation of what is as subject matter and what is not as form. Of course, these two essential aspects of any particular picture or poem are inextricable as experienced by the viewer or reader. But in our activity as makers, we gauge subject matter and form as distinct facets of the whole, in order to shape with discipline and purpose. Such was the explicit effort of Stevens, who, over a long career, pondered the individual imagination as a creative (and, notably: decreative) faculty that could in various ways manage (but never resolve) the tension between what is and what is not — an active capacity consequential both in poems and in life.

If your goal is to make significant, enduring things, then, as far as I can tell, the whole deal resides in the quite rigorous use of your imaginative gift to get at the ineffable (what is not), rather than to portray what is already effable. Beware, though: because of our fundamental limitations, the aesthetic object — your work — will necessarily fail both the possibilities of your mind and the givenness of the world; I hope to persuade you not only that this is okay but that one’s humanity depends upon these near-misses.

Given all that, it’s easy to see that ‘the ineffable’ and ‘the self’ are, for my purposes, synonymous. But what I’d like to suggest (by working backward from the aesthetic object) goes further: that ‘form’ and ‘self’ are pretty much identical as well. We are nothing but form-making creatures, each of us a one-off, perpetually knitting inner to outer (while simultaneously unraveling it all) to fashion a kind of idiosyncratic day-to-day, hour-to-hour livability of our given lot. Which then somehow, over time, becomes a singular personhood. (You might notice that, by analogy, ‘self’ equates with what is not, and so we’ll need to talk about that, too.)

Shifting our attention outside: the stuff of reality is stubborn, recalcitrant. It will never meet us in the ways we might wish. Thus Valéry’s revolt against facts. Fortunately, blessedly, we do have moments of vivid experience when interior and exterior come into a sort of tentative alignment, as if they’re neurons between which a synapse has miraculously fired. Calling these ‘epiphanies,’ we rejoice in the mere suspicion of transcendence.

And, inevitably, we despair: the ephemerality of these revelations is a painful echo of our own mortality. Yet, strangely, it is this great brokenness of self that compels some of us to make an object out of such a moment — not a thing that is ‘about,’ as in recollection, but rather something that is the very cry of its occasion, “the poem as it is, / Not as it was,” as Stevens would have it.

To do this, we find ways to short-circuit the cognitive feedback loop — the ceaseless calibration of the inexhaustible need within and the unrelenting resistance without — to arrest the existential frustration, if only for an instant. To adapt Iris Murdoch’s formulation, we ‘unself.’ This is Montaigne, earlier than Murdoch, on that topic:

Cicero says that philosophizing is nothing other than getting ready to die. That is because study and contemplation draw our souls somewhat outside ourselves, keeping them occupied away from the body, a state which both resembles death and which forms a kind of apprenticeship for it; or perhaps because all the wisdom and argument in the world eventually comes down to one conclusion; which is to teach us not to be afraid of dying.

I believe that using a camera can draw us away from our selves. That it is a meaningfully constrained way of thinking and knowing that enables us to conjure relationships among otherwise uncooperative earthly things; new and valuable correspondences which never actually existed. That these novel sets of relationships — called ‘photographs’ — are useful because of the independent authority they possess to both defy and embrace impermanence and to convey to other human beings the essence of a separate self’s fleeting and often furtive connections with the obstinate thusness of it all. In short, that such pictures can get us about as close to the ineffable as our mortal shortcomings will allow.

And what’s more: working with the camera has the warrant to turn this whole fearful mess on its head: to demonstrate that humility in the face of the actual and the transient has the paradoxical power to effect a true and earned freedom. That it authorizes ultimately the affirmation of life, the final yes.

This is what I want to tell you: to photograph is to learn how to die.

About the author

Tim Carpenter is a photographer, writer, and educator who works in Brooklyn and central Illinois. He is the author of several photobooks, among them A month of Sundays (TIS books); Christmas Day, Bucks Pond Road (The Ice Plant); Local objects (The Ice Plant); township (TIS/dumbsaint); Bement grain (TIS/dumbsaint); Still feel gone (Deadbeat Club Press); The king of the birds (TIS books); and A house and a tree (TIS books). Tim received an MFA in Photography from the Hartford Art School in 2012. He is a faculty member of the Penumbra Foundation Long Term Photobook Program and a mentor in the Image Threads Mentorship Program.

Win a copy of Tim’s book

I’m teaming up with The Ice Plant to give away a copy of To Photograph is to Learn How to Die to one of my readers — Tell me why you love photography in the comments for a chance to win. I’ll draw a random winner from the comments on July 21, 2023. I’m looking forward to hearing from you!

One more thing…

If you follow me on Instagram, you know I’ve been exploring IG’s new Threads app. I’m having fun with it and would love to connect with those of you checking things out over there. It's fun, filled with images, and I'm meeting new creative people every day. Quite a few photographers are hanging out already. Who knows, it may become a new place for creative conversations. Drop me a line!

To photograph is to breathe, be calm and solely focus on one subject. It is a peaceful moment in time that can lead to ‘Le Petit Mort’ on occasions. It is Love, Passion, Desire yet also intense Grief, Loss and Sadness. It is such a deep personal, intimate account of self reflection and personal choice. To photograph is to Be.

Currently, I am putting together a book of photographs and text about my later mother. Somehow photographs from pre-Holocaust Europe survived and made their way to Australia where I live. As I select and place many of these photographs into the book publishing software, I have many times looked intensely at the just-pre-war photographs of my mother and am drawn into a reverie about her life then and her beauty, and the knowledge that she could not know what horrors were about to befall her and her entire family and community. So, as I read the excerpt from Tim Carpenter's book, I felt the full force of his understanding of what is and what is not.