Charles H. Traub's Do's and Don'ts

A photography teacher's lessons for inspiring lens and screen artists

There’s no right or wrong way to do photography.

Still, plenty of people teach it, so it’s worth considering advice from those who know. The medium is ever-changing, which is why it’s so exciting. And the question is, how to do it well? Is there a formula or a set of rules? Maybe, and maybe not.

I met Charles Traub when he invited me to New York to serve on the Aaron Siskind Foundation judging panel in 2016. That was a thrill because I worked with Deb Willis and Vince Aletti, two bona fide photography legends. It was a long, image-filled day, and after we finalized our selections, Charles took me to the Strand Bookstore — my first time inside that hallowed place. Afterward, we hung out on his front stoop, sipping wine, eating cheese, and talking pictures.

Suffice it to say, it was a lovely afternoon and a day I’ll never forget.

Charles is one hell of a photographer. He is wildly productive and constantly sends me project updates. I love hearing from him because I know I’ll see something cool when I open his emails. That was the case when he wrote me recently to share a new piece of writing. Actually, it was a revised piece of writing. He described it like so:

I thought you might be interested in my Dos and Don’ts — all a bit tongue-in-cheek. This list was inspired by my cantankerous teacher at the Institute of Design, Chicago, Arthur Siegel. I first readdressed his “rules” in 1984 and re-edited them in the mid-90s; now, this is the 2024 edition.

There is a lot of good stuff here — some of his notes will make you smile. I asked Charles if we could publish it, and he graciously agreed. Like all rules, these are meant to be broken. They’re also a lot of fun. I suspect some of them will resonate.

Let me know what you think of these Dos and Don’ts. If you know someone who would appreciate it, please share this link with them. Okay, take it away, Charles!

The Do’s

Do something old in a new way.

Do something new in an old way.

Do something new in a new way. Whatever works… works.

Do it sharp; if you can’t, call it art.

Do it on the computer — if, by any conceivable way, it can be done there.

If it can be done digitally — do it.

Do fifty of them — and you will definitely get a show.

Do a four-hour video — and you may get a show, but no one will stay.

Print it big, or project it big, and if you can’t, at least do it red.

If all else fails, turn it upside down, and if it looks good, it might work.

Do celebrities — if you do a lot of them, you’ll get a book.

Never go out without a camera — a good cellphone will suffice for both still and moving.

Learn how to see by making images.

Help others learn how to see by making images.

Take lots of images and make lots of footage, but edit it — less is more.

Practice taking images, editing images, and discarding most of them.

Edit it yourself.

Edit: when in doubt, shoot more.

Edit again.

Design it yourself.

Publish it yourself.

Learn to look at others. You already know about yourself.

Learn to look at places you’ve never looked at.

Connect with others — network.

Read Darwin, Marx, Joyce, Freud, Einstein, Benjamin, McLuhan, Barth, Arendt, Sontag, and Mulvey.

See Citizen Kane ten times.

Bend your knees.

Look up, look down, look sideways, look backward.

Wander… keep looking and keep looking.

Look at everything — stare.

Construct your images from the edge inward.

If it’s the “real world,” do it in color.

Be self-centered, self-involved, and generally entitled and always pushing — and damned to hell for doing it.

Break all rules except mine.

The Don'ts

Don’t do it about yourself — or your friend — or your family.

Don’t dare photograph yourself nude.

Don’t dare photograph your own apartment.

Don’t look at old family albums — you might learn something by looking at others’ albums, videos, or films.

Don’t artificially color it — or write on it.

Don’t put more than four lines of text in a video.

Don’t use alternative processes, deliberately deteriorating your film — if it needs any adornment, at least do it on the computer.

Don’t gild the lily — AKA less is more again.

Don’t use computer-generated glitches; while often abstract, it is only just that — a glitch.

Don’t go to video when you don’t know what else to do.

Don’t record indigenous people, particularly in foreign lands; at least ask them for permission.

Don’t whine, produce.

Some More Not To Do’s:

Photograph dust, particularly avoid it in your grandmother’s house.

And your grandmother — certainly not when she is sick and dying.

Adolescent girls sitting or resting on their beds expressionless.

Adolescent girls, in grass fields, standing on beaches, or in pools of water, expressionless.

All adolescents, particularly gathered in a swimming hole looking forlorn.

Cats.

Goldfish.

Food you have eaten.

Food you are about to eat.

Looking out your window pensively.

People wearing masks.

Yourself, nude. Your lover, nude. And certainly not yourself in any way.

People looking at art (unless they are looking at yours).

Make a big print just because you can.

Put tape on it.

No suburban houses with lawn ornaments or children's toys.

Rusty cars, rusty signs, rusty bridges, rusty anything, forget about it.

Detritus on cracked pavements, especially shot from above.

Old books, stacks of books, ripped books, and libraries in general.

Stark portraits against a white background, black and white, or color.

Use the abstracted, montaged, cubist assemblages of junk, old photographs, or new photographs.

Collages of your photographs — they are not necessarily synergistic.

Assemble your photographs as an installation on the floor.

If the image or film has to be explained in more than ten words, it's likely not an image but an illustration. *A vague metaphysical-sounding explanation will not serve.

The Truisms

All imagery is meaningful in the right context at the right time.

Sooner or later, someone will say it is art — but if the curator says it is art… it must be art.

The lens image is always a historical document.

One picture is not worth 1,000 words, and if 1,000 words tell us little, 1,000 images tell us something.

Any photographer can call themselves an artist — but not every artist can call themselves a photographer.

Compulsiveness helps; Neatness helps, too; Hard work helps the most.

The style is felt — fashion is a fad.

Remember, it’s usually about who, what, where, when, why, and how.

It is who you know. It’s good to know a curator.

Installations from found detritus may be mistaken by maintenance personnel for garbage. *Images of garbage may be indeed just that.

Many a good idea is found in a garbage can.

But darkrooms are dark… and dank…fuhgeddaboudit.

Avids are too cumbersome.

Expose for the shadows and develop for the highlights — Or better yet, shoot digitally.

The best exposure is the one that works.

Cameras don’t think; they don’t have memories — digital cameras have something called memory.

Learn to see as the camera sees; don’t try to make it see as you do.

Remember, a good digital point-and-shoot is just as fast as a Leica — and the new video cameras are a hell of a lot lighter than their predecessors.

Though the computer can correct anything, a bad image is a bad image. If all else fails, you can remember, again, to either do it large or red — Or tear it up and tape it together.

It always looks better when framed on the wall.

If it doesn’t sell, raise your prices.

Self-importance rises with the prices of your work — A dead artist's work is always more valuable than the work of a living one. You can always pretend to kill yourself and start all over. (See the film The American Friend)

Good work gets recognized sooner or later — there are many good photographers who need it before they are dead.

If you walk the walk, sooner or later, you’ll learn to talk the talk — If you talk the talk too much, sooner or later, you are probably not walking the walk (don’t bullshit).

Photographers are the only creative people who don’t acknowledge their predecessors’ work — if you imitate something good, you are more likely to succeed — Whoever originated the idea will surely be forgotten until they are dead. Corollary: steal someone else’s idea before they die.

All artists think they’re self-taught, and all artists lie, particularly about their dates and who taught them.

No artist has ever seen the work of another artist (the exception being the postmodernists, who’ve adapted appropriation as another means of reinventing history).

Critics never know what they really like. They are the first to recognize the importance of what is already known in the community at large. The best critics are the ones who like your work.

Theoreticians don’t like to look — they’re generally too busy writing about themselves. Given enough time, theoreticians will contradict and reverse themselves.

Theoreticians who find that something works in practice will then pose it has a theory — Practice does not follow theory; theory follows practice.

The curator or the director is the one in black, the artist is the messy one in black, and the owner is the one with the Prada bag.

The gallery director is the one who recently uncovered the work of a forgotten person.

Every gallerist has to discover someone, every curator has to rediscover someone, and new galleries have to discover old photographers.

Galleries need to fill their walls — corollary: thus, new talents will always be found.

Gallerists say hanging pictures is an art.

There are no collectors, only people with money.

Anyone who buys your work is a collector — your parents don’t count.

The best of them is the one who shows your work.

Every generation rediscovers the art of photography.

Photography history gets reinvented every ten years.

Video has a relatively short history, but much of its earlier works are only just recently being rediscovered.

All photographers are voyeurs; admit it and get on with looking.

Everyone is narcissistic; thus, anyone can be captured with the camera.

You are certainly a narcissist if your work is about yourself.

The lens and screen arts are about looking.

Learning how to look takes practice.

Serendipity, coincidence, and change are more interesting than any preconceived constructs of our human encounters.

The character of the image-maker is tied to the compulsion to rediscover oneself in their art.

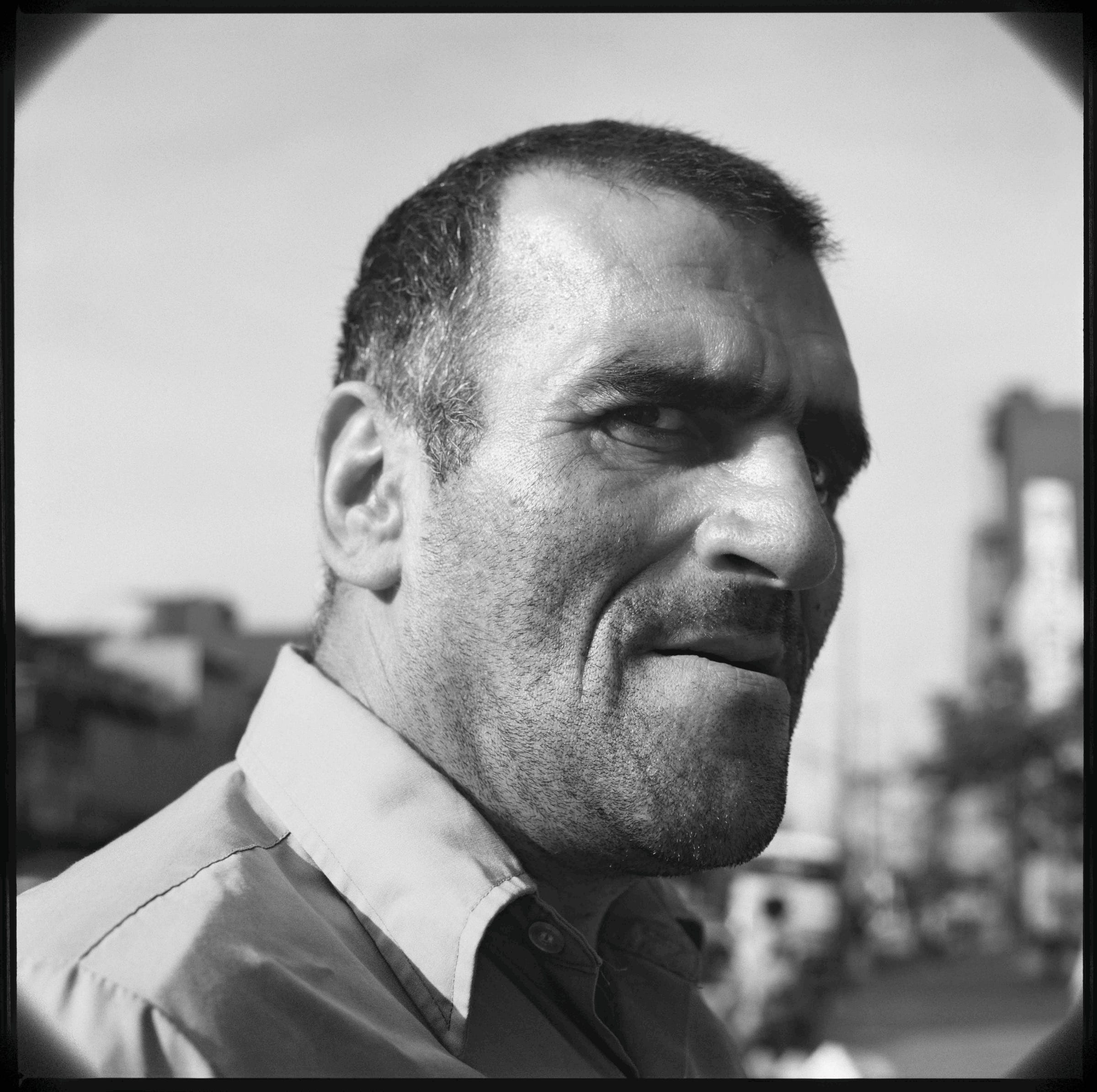

About the author

Charles H. Traub has been a photographer and educator for over 50 years. His work is represented in major museums and collections around the world. In 1988, he founded the MFA program of Photography, Video, and Related Media at the School of Visual Arts in New York City and still serves as its Chair.

Formally, he was a founder of the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College, Chicago. Later, he directed New York’s prestigious Light Gallery and was president of the Aaron Siskind Foundation for over 25 years. Traub has received numerous awards, including the prestigious ICP Infinity Award, for his work on Here is New York: A Democracy of Photography.

He has published 17 books, including 11 monographs of his own. Recent publications include Dolce Via Nova (2014), Lunchtime (2015), No Perfect Heroes: Photographing U.S. Grant (2016), Taradiddle (2016), Tickety-Boo (2021), Vacant (2022) and Skid Row (2023).

Find him on Instagram @charlestraub.

One more thing…

I’ll leave you with this: iidrr Gallery released In the Realm of Charles Traub, a documentary about Charles, his work, and his thoughts on what he calls “lens and screen arts” last year. It’s an excellent portrait of one of our great living photographic artists. I enjoyed this and think you will too. Thanks again, Charles!

Absolutely fantastic.

Haha, love it Andy! But what are we doing if not photographing dust in grandmother’s houses ;)

“I kick up the dust so I can see the light” — W Eugene Smith maybe??