Aaron Turner: Moves from the Archive

Jon Feinstein talks with the photographer about history, family, and the creative legacies of Black artists

And now for something completely different.

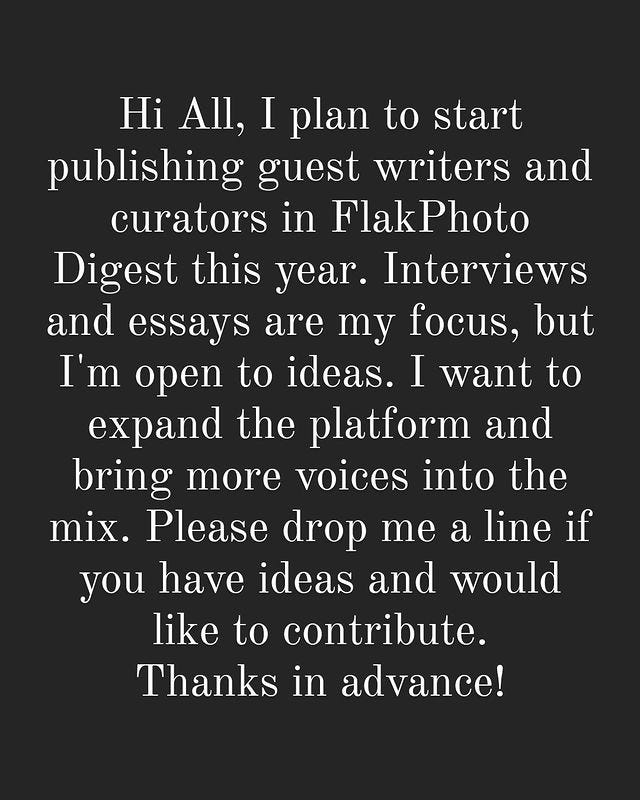

I told you in my previous post that I would explore new ideas in year two of FlakPhoto Digest. Last year, I dabbled in bringing other photographers’ voices to the foreground — Tim Davis talked about his photo safaris, Greg Miller recorded a story about one of his earliest photographs, and Dawoud Bey wrote a reflection on Richard Avedon’s In the American West. Those were fun experiments, and I want to do more things like this here moving forward.

This week’s post is something entirely different: a conversation between two artists and a collaborative beginning for FlakPhoto Digest — our first interview!

Jon Feinstein is an old friend I met online years ago and whose work has always been a beacon for me. Jon co-founded Humble Arts Foundation in 2005, and he’s been a steady presence in the photoland community ever since. When Ben Alper emailed a while back to announce a new book from his imprint, Sleeper Studio, I was intrigued because the photographer he had published was Aaron Turner, an artist I met while curating the Center for Photography at Woodstock’s Photography Now exhibition in 2020. It’s fun when creative worlds collide, and I was delighted when Jon pitched me on publishing an interview with Aaron about his latest book.

I enjoyed working with these guys on this piece, and I learned a lot in the process. These are different pictures than I usually show, and I appreciated opening my eyes to a new perspective. Aaron is an intriguing artist, and he has much insight to impart. As always, I’d love to hear your feedback, so please feel free to share your thoughts when you’ve finished reading. Take it away, guys!

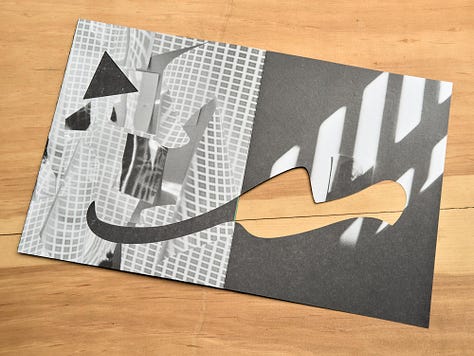

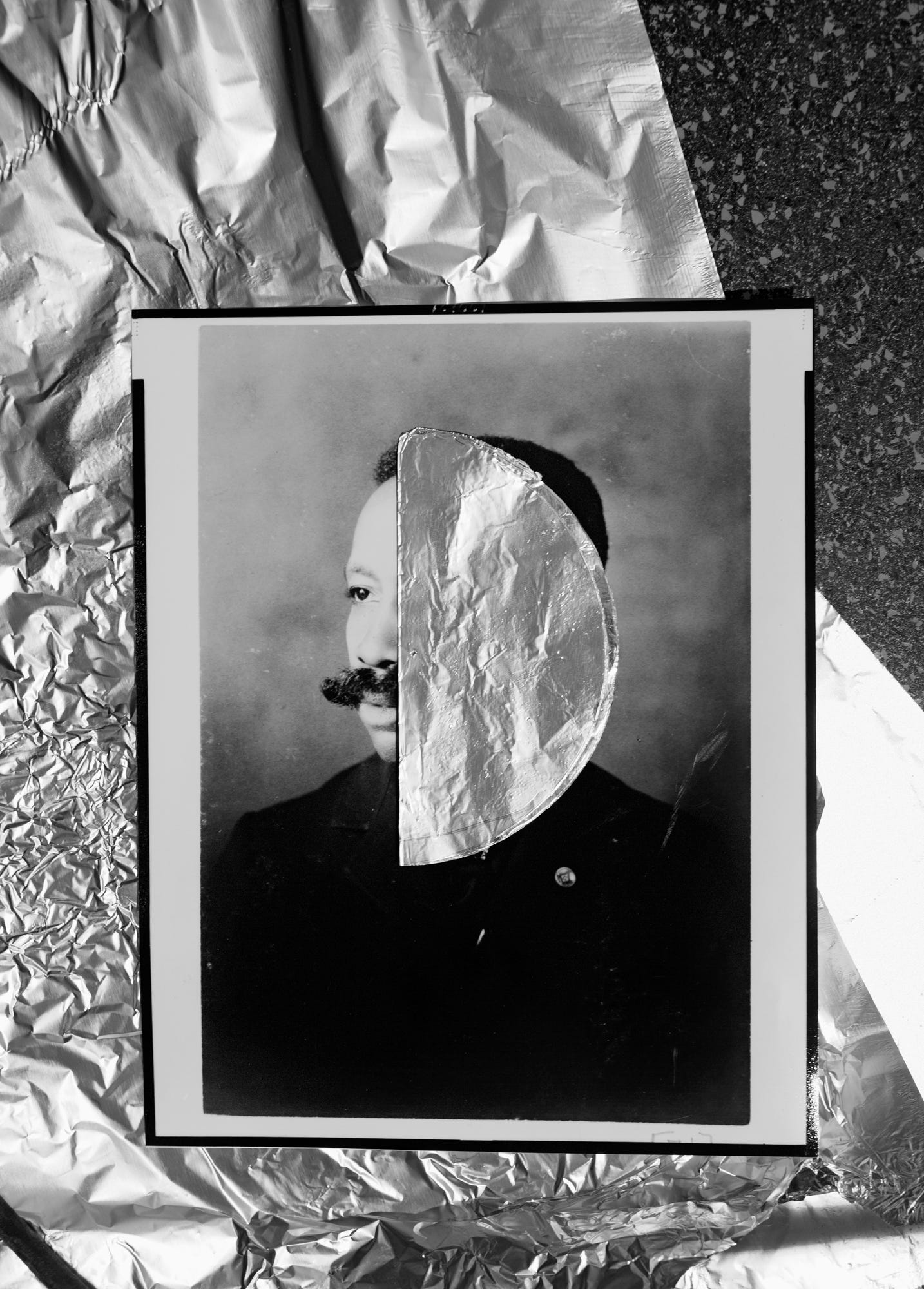

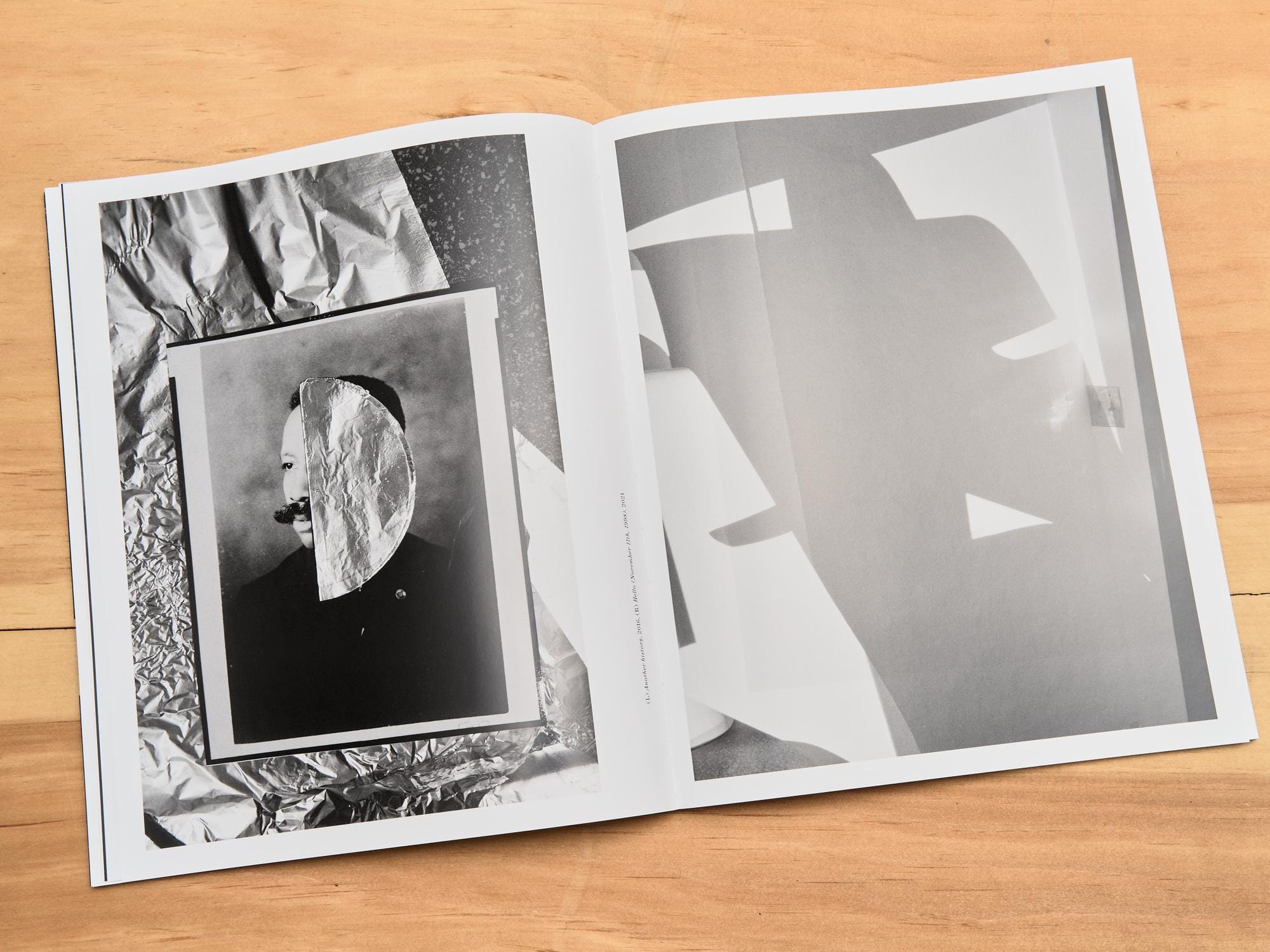

Opening the cover of Aaron Turner's new book, Moves From The Archive, is delightfully disorienting. It unfolds from left to right, punctured by jagged cuts that make you slightly afraid you might accidentally rip it apart. And at first, you're not entirely sure what you're looking at. Shimmery materials, grid lines, and splotches of paint gradually pull you in and unravel the meat of the book. When that unraveling happens, the experience becomes slightly more grounded yet mysterious.

Turner journies through historical portraits of Frederick Douglas, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X, self-portraits, and photos from his family archives. He reimagines them with physical, sometimes sculptural depth, cutting, projecting light, and collaging them with mirrors, cloth, cellophane, and packaging materials. And then, he rephotographs them, which creates a new sense of space and visual confusion. It's an abstract and open-ended way to engage with history, Aaron’s family, and the legacies of Black artists – one that raises new questions with every page.

A long-time fan of Turner's work and unique way of seeing, I reached out to learn more. — Jon Feinstein

Jon Feinstein: Going back in time for those unfamiliar with your work: how did you get into photography and what moved you into this hybrid of – let’s create a new term for it – ”appropriative history-sculptural photography”?

Aaron Turner: I first got into photography in my undergrad years, majoring in journalism. I thought I'd take a Black & White Darkroom course to deepen my understanding of the medium just a bit more than taking images for the campus newspaper. I've been doing it ever since.

As the years went by, I continued working with newspapers and freelancing. I was always interested in who took pictures for which publication. I'd go down a rabbit hole of their website, find out where they went to school, etc. Though I had a journalism background, there were just as many other freelance photographers with art backgrounds.

Around this time, I also began dabbling in art myself and went on to get an MFA. It was a different way of seeing the world.

What about the MFA made seeing different for you?

I merged my analytical and research skills from journalism with conceptual art-making approaches. Along the way, I started realizing what I was drawn to, like geometric abstraction, repetition, form, and space, concerning specific art history themes and American history, where my hybrid style now comes from.

Getting into your latest work a few years ago, you talked about re-examining yourself in the context of art history, specifically, Black American art history, and honoring those who came before you. And you’ve kept going with it. How has that broadened, shifted, and enriched how you think about these ideas?

I'm still of that same mindset. I'm constantly reviewing art history at my own pace, looking at what's happened in the past compared to what's happening now, and understanding who received recognition and who didn't.

One body of work I've been exploring most recently is Seen of light and legacy. I'm looking at the narrative of Frederick Douglass as the most photographed person of the 19th century. It fascinates me, and I want to make work about it.

Artists like Howardenna Pindell, McArthur Binion, and Mel Edwards come from a specific generation of Black artists working in abstraction, which was not the most popular form to be working in the 1960s/70s. They faced a lot of challenges but never deviated from their interest. That's what being an artist is to me. Now, their work is being shown more than ever. It's just interesting how time works.

I want to bring awareness to what came before me in the field.

As a book, this work takes on a whole new life. It was already sculptural, but the way you laid it out with Sleeper Studio, the physical cuts into the paper, and the foldouts give its sculptural-ness a tangible third dimension. Can you talk about these design decisions?

The cut-out shape in the front of the book is one that I made a few years ago, in 2020. I was working on a set of images called Black Alchemy: if this one thing is true, which also became a book. I took black plotter paper, cut the shape out, and used the positive and relief of that cut as props in a few photographs. I still have this same original cut-out hanging in my studio today.

Shortly after, I found out about Frederick Sommer. He had a set of black and white photographs documenting cuts he made in butcher paper using a utility knife. It was very similar to how I was working. I began doing the paper cuts to develop a way to make fast, unique shapes in the studio for setups.

The one that appears in the book was one of the first that felt special to me, so I kept it around and knew I'd use it later. The designer, Elana Schlenker, came up with the tri-fold cut idea. I'm always looking for ways to share the intimate space of the studio environment with the audience.

I love Elana’s work and how she helps bring new layers to every artist she collaborates with. Looking more at your writing, I’m interested in your use of the term “draws a parallel between racial passing and abstraction.” Can you dig into this as it relates to this work?

That wording speaks particularly to a group of ideas I'm working from, going back to the origins of Black Alchemy.

Going back to the Black artists working in abstraction in the 1960s/70s, I mentioned earlier and the obstacles they faced in pursuing art. For example, I remember reading this article titled The Changing Complex Profile of Black Abstract Painters (2011) and being drawn to the following Howardenna Pindell quote:

“I remember going with my abstract work to the Studio Museum in Harlem, and the director at the time said to me, ‘Go downtown and show with the white boys,’” says Pindell, adding that William T. Williams and Al Loving met with the same kind of response. “We were basically considered traitors because we didn’t do specifically didactic work.”

Before that, I came across Frank Bowling's essay, It's Not Enough to Say Black Is Beautiful (1971), where he talks about the perception and reading of Black artists working in abstraction beyond anything other than didactic; I also like to think the title was addressing the expectation for Black artists to depict the Black experience, hence The Black Arts & Black Power Movements.

In a 1926 essay by Langston Hughes titled ”The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”, he writes about a young Black poet questioning his identity, wanting to be known simply as a poet and not a Black poet. Hughes' interpretation of what the young poet had shared was that he wanted to be a white poet. The 2008 Art 21 clip with Kerry James Marshall shows you what is spoken about here.

Kerry James Marshall is no stranger to the topic of passing in his work. In 2020, he made a set of paintings addressing the speculation of John Audubon's identity. In an intentional gesture addressing the identity of John Audubon, David Driskell included a painting by him in the exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950.

Other artists such as Glen Ligon, who created Study for Passing (1991), Adrian Piper's Self-Portrait as a Nice White Lady (1995), and Howardena Pindell's Free, White and 21 (1980), currently on view at MoMA.

In American History, you have the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896) and Nella Larsen's novel Passing (1929).

I list all of these examples to make the point that the illusions of what a Black artist is supposed to produce are coded in my aesthetics, the presence of the shape, form, repetition versus the figure, and simultaneously the presence of both.

I liken the perceptions of Black artists using abstraction to what the benefits of passing afforded Black Americans during pre-integration, just as in Langston Hughes' rebuttal to the young poet and the conclusion he wanted to be white, or the response Howardenna Pindell’s work and others that somehow abstract work was only for white artists, and the perception that those paths would allow an unscathed path forward, is simply more complicated than that.

This book was originally going to be titled Black Alchemy, which has since broadened to Moves From The Archive. What inspired the title change?

It could have been called Black Alchemy by default, but I wanted something different. The inspiration for the title Moves From The Archive comes from the trajectory of Black Alchemy Volumes 1, 2, and 3. Each builds on the next; each is essentially a separate archive I pull from to create the next volume.

To your point, and in a broader sense, it’s interesting to think about this work beyond just remixing or giving “expired” images a new life. It’s expansive and holistic. A broad and complex puzzle of your relationship to your family, culture, memory, and photography as a physical, tangible form and process.

I agree 100%; it goes beyond giving expired images a new life. It's one of the reasons I avoid words like archive or collage when speaking about my work.

I closely identify with archives within the last two years or so, and I'm more drawn to that description than I am to collage. I can't control what people say. That's just how the world works. People choose words that are closest to something they are trying to understand. It's human nature, and we can't help it.

That's a good in-between space for art to land and to speak about things such as family, culture, memory, photography, the tangible, process, etc.

Artists pick up a particular medium to not speak about the medium most times and also not express themselves in the way it's often understood. It's more about communicating a narrative, an idea, or the best way to tell a story. Things get lumped into categories just as an easy way to organize something.

I use photography, abstraction, painting, light, sculptural materials, and space to discuss more complicated things like history, desire, conformity, identity, relationships, etc.

I don't care about winning an argument or convincing anyone of anything; the work starts for me in my studio, but when it leaves the studio, it takes on a life of its own. It's out of my control what people think, but as long as it's making people think in the first place, is more so what I'm after.

I feel this way from studying artists such as David Hammons, Adrian Piper, and Stanley Brouwn. I encourage everyone to take a look at these.

For personal reasons, the Alzheimer’s connection to this work, specifically how you visualize the blurriness of memory, hits me hardest. Is this still a major piece of the work for you?

Thanks for bringing this into the conversation. I'd say Alzheimer's is still strongly connected to the work, thinking back to seeing both of my great-grandmothers suffer from it.

Does this work resolve any of the blurry issues around memory for you? Or does it create further mystery?

Memory is like a projected film reel that plays repeatedly in our heads every day, especially when we have idle time. I sometimes battle memories because I'm trying to be creative in the studio, and they get in the way. Other times, I need them for inspiration.

We exist in the present, but it's helpful to be directed toward the past occasionally.

One thought that creates mystery around memory is understanding that outside of written accounts or maybe films, we'll never truly know how someone else imagines or visualizes something. Yes, we make representational pictures or objects of how we see something, but I'll never see it the same way the next person does. Pulling from that space creates interesting perspectives.

Does the publication of this book mark an end or give you a sense of resolve to the unanswered questions the series raised for the past decade?

This publication is like an album. It contains all three volumes of Black Alchemy, and my first two books are like an EP or LP. I like music and draw inspiration from it. I'm currently moving in a direction to address those ideas.

It's more of a continuation than an end. I am still working on Black Alchemy Vol. 3, and I'll most likely continue using the camera and making pictures that way, adding and taking away along the journey.

Specifically, thinking about this work in book form, what do you hope readers come away with?

With the book's physical form, I hope it represents something to hold on to and reflect on. I hope people revisit the text as often as needed. I don't anticipate what readers come away with; as long as the work sparks curiosity, that's good enough for me.

I know that time plays the most critical role. Someone five, ten, fifteen years or more down the road, coming across the book will be more meaningful. I hope they take what I did and continue adding more.

Aaron Turner is a photographer and educator currently based in Arkansas. He uses photography as a transformative process to understand the ideas of home and resilience in two main areas of the U.S., the Arkansas and Mississippi Deltas. Aaron also uses the 4x5 view camera to create still-life studies on identity, history, blackness as material, and abstraction. Aaron received his M.A. from Ohio University and an M.F.A from Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University.

Jon Feinstein is a photographer, curator, writer, and the co-founder of Humble Arts Foundation. He has dedicated his career to helping emerging photographers get eyes on their work through exhibitions, publishing, educational, and marketing initiatives. His writing appears in Vice, Aperture, Photograph, Hyperallergic, Adobe, and various other publications, and his personal work has been widely exhibited and published. Jon’s first solo exhibition opens in Seattle at Solas Gallery on October 5, 2023.

Moves from the Archive is available from Sleeper Studios in an edition of 500 copies.

Such interesting work. Thanks for the introduction to Aaron!

Really interesting work, nice interview. A very talented young man!